The gap between strategy and execution is an enduring problem in business. What’s more, this disconnect is often a cause of significant waste — of time, money and employee energy. And while we can try to overcome these challenges through workshops or process reviews and audits, such attempts often compound the issue. At its worst it can damage organizational culture.

So, how can we correct this? In this blog post we’ll explore how organizations can better connect strategy to implementation and ensure those discussions and initiatives actually deliver lasting value.

Identifying the causes of strategic disconnection

Before we explore what can be done we first need to look at the causes of the disconnect between strategy and execution. Based on our experience with many different kinds of clients, these are always upstream of specific initiatives or workshops. So, getting to grips with these root causes gives teams and organizations a far better chance of ensuring that any strategy conversations and work has a tangible and sustainable impact.

We see there being four key symptoms of disconnection, all of which have discrete but equally important causes. Let’s take a look at them now:

Strategy and execution teams ‘don’t get each other’ — it feels like they are pulling in different directions because there’s no common standardized language and because of incoherence between levels of hierarchy, regions and functions.

Strategy is defined with little to no connection to the downstream process — sometimes a strategy document is viewed as a goal in itself, not as a step towards that goal.

Improvement metrics aren’t connected to strategic organizational goals — Product team metrics are sometimes retrofitted to the business objectives or focus on the product instead of the customer.

Shared functions (like finance or technology) wield outsized influence over strategic decisions — while this is sometimes helpful in the short-term, it means decisions are made without accounting for organizational needs in a more holistic manner.

None of these issues are easy to solve. They all require the effort of the majority of the people in the organization to build a view of the organization.

Let’s dive deeper into how that can be done.

Defining and clarifying your business architecture

It’s vital to consolidate and clarify the multiple terms flying around in the organization to describe different things. This includes just about everything: capabilities, capacity, goals, aims, objectives, processes, activities, tasks, strategy, business direction.

In our experience, not only have we noticed just how many different terms organizations are trying to handle, we’ve also noticed it’s common for many to be used interchangeably. So, instead of our business architecture — the elements that make up an organization from how it works to how it talks about itself — being a source of stability, it instead increases confusion.

We recommend a simple set of principles to define terms not just to describe the architecture, but also to guide the language of the actual capabilities and processes:

Don’t reinvent the wheel. Start with industry standards. Carefully evaluate what's already available as an industry standard and use it as a default to begin with before deciding to start from scratch. The International Standards Organization (ISO) has already done a lot of work in consolidating the language around this space, as part of ISO:19440.

Use plain language everyone can understand. Even if ISO has done a lot of the groundwork, there is a lot that can be done based on those standards to make the language simpler, and clearer. For example, ISO defines a capability “Business Implementation Management” which we typically recommend our clients to just call “Strategy Management”.

Involve your people from the start with clear rationale: If you are already dreading the messy debates that could happen from this exercise, you’re not far off the mark. These are difficult conversations that take a lot of patience and time to get through. However, any siloed system will need exactly these types of conversations to happen if any progress is to be made. Encourage these debates and channel them toward designing a base model.

Three basic concepts

We’ll need to define three basic ideas to get started.

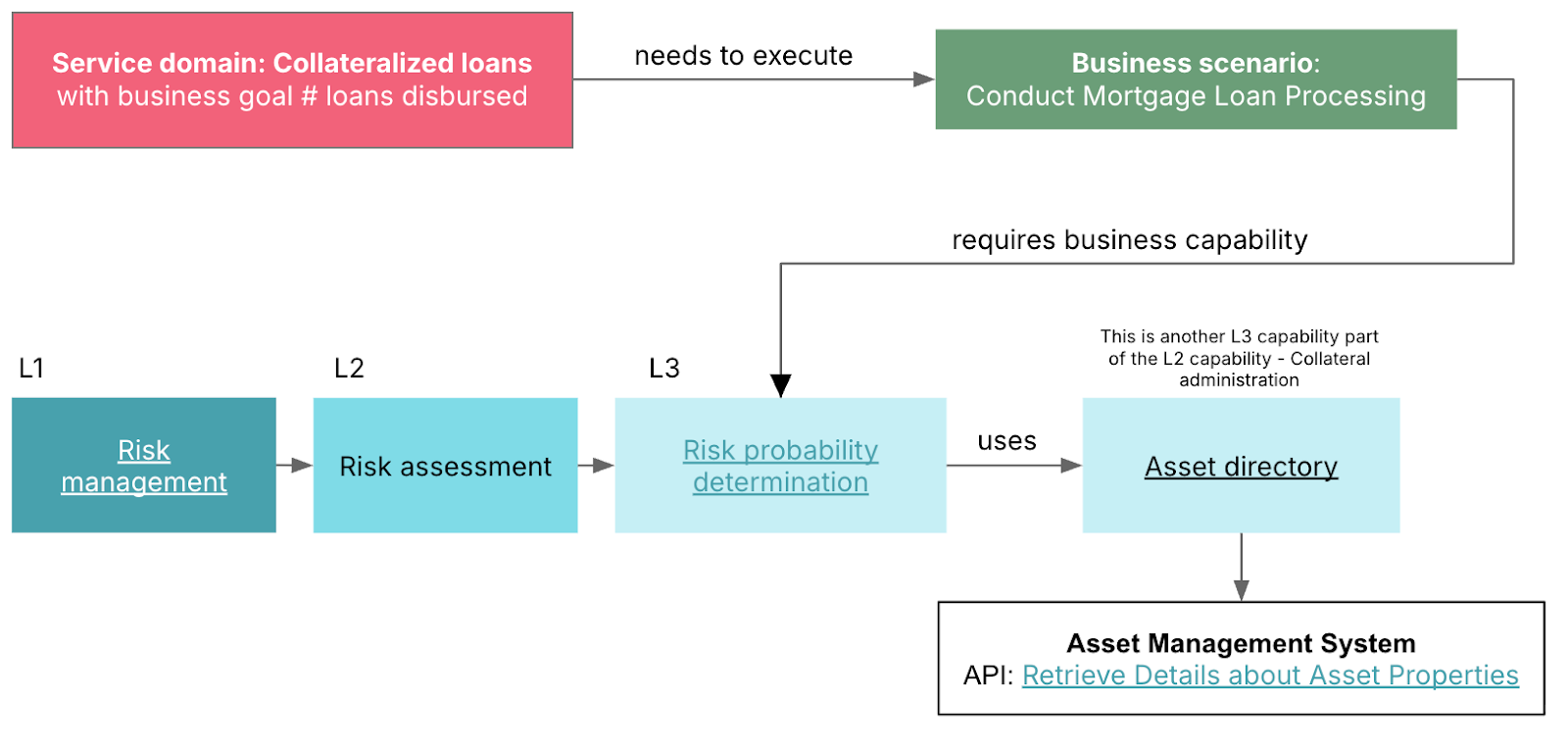

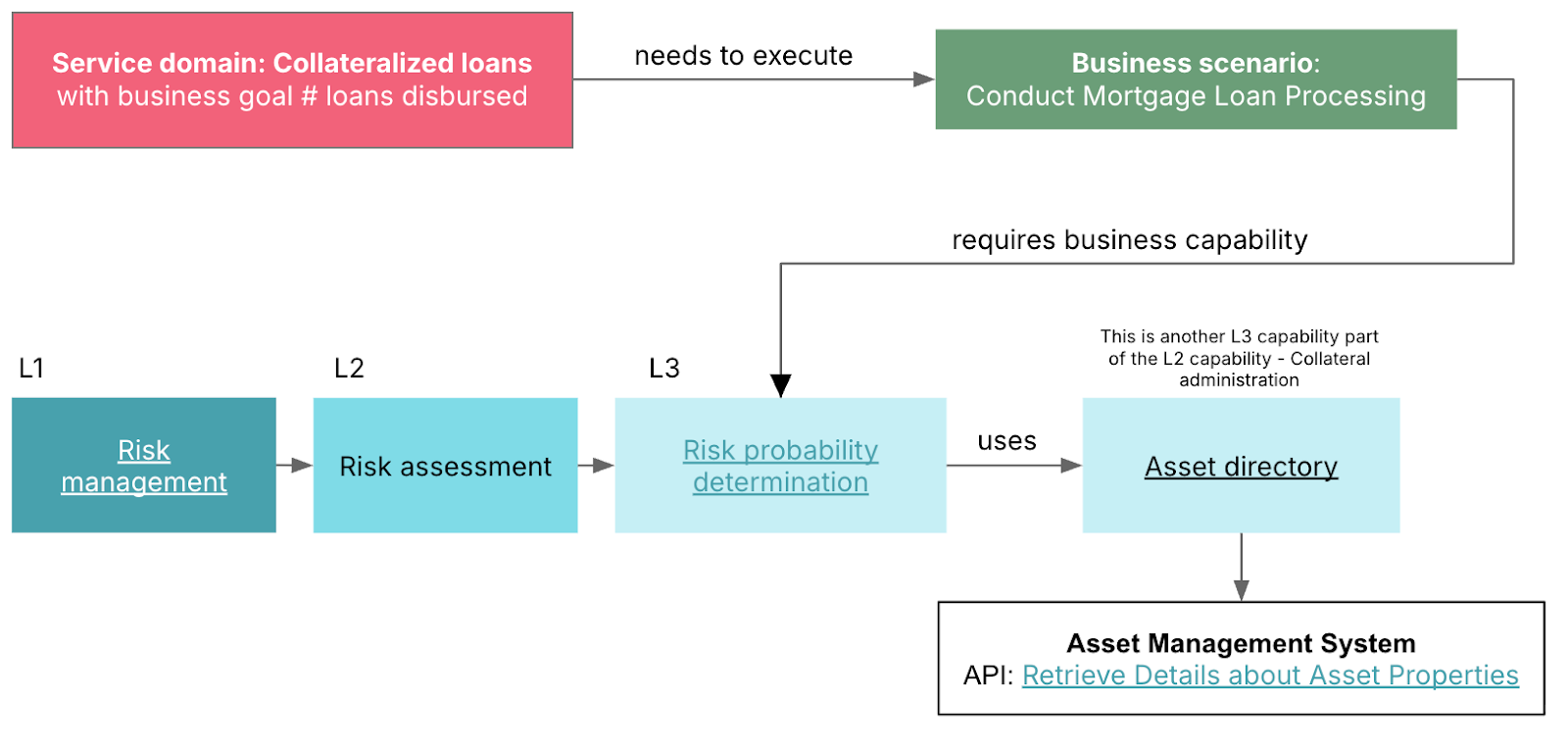

Service domain: a logical grouping of related business scenarios and capabilities within a company with a clear set of goals.

Business scenario: What each service domain needs to execute to achieve its goals.

Business capabilities: What’s required for a service domain to execute on a business scenario. These are technologies (cloud storage; a billing system) or particular skills (architecture; accounting).

If we are to have productive conversations across the organisation, we will need everyone to first be aligned on these three terms. They form the basis of the business architecture required to align strategy and execution.

TIP: Create a clear, short document which can be circulated and outlines examples from your business to act as a reference and provide clarity. Make it easily accessible by sharing in your organisation’s knowledge management tool or system.

This process of definition and related mapping should provide us with visibility on just what business capabilities are used by which parts of the business. More importantly, we also now will have standard language that will eliminate misunderstandings and redundant work by multiple teams working across the organization.

How does this drive the business?

Creating a holistic view of the business is valuable because it helps us to visualize the connections between high level business goals to implementation — which could be a process, a skill, or even an API.

Once we have certain artifacts in place — like, say, an OKR document, Lean Value Tree, architectural diagrams or standard operating procedures set of Standard Operating Procedures, Technology Architecture, a People plan and a Business Capability Map, there are further connections we need to draw.

This should be done like this:

Create a list of all business capabilities tagged to the lines of business that depend on them.

Map all the processes that depend on each capability.

Consolidate similar processes across regions, business units and functional units.

To demonstrate, this is how it might look in practice. Imagine an example of a mortgage loan processing.

As you can see, there’s a connection between an API that’s part of the system that supports the asset directory capability. This helps the business achieve its goal of number of loans disbursed. We can similarly map all other tactical and technology factors that will affect that goal.

These views above give us direction on strategy. They show us what capabilities we need to nurture. However, it doesn’t stop there; it also tells us what business scenarios need to be examined further for consolidation or optimization. Although doing this for the first time can be complicated, it will drive clear visibility from strategy to execution (in all the three lenses of people, process and technology) across even the most complex of enterprises.

In our experience, tackling service domains and business scenarios is something organizations find fairly straightforward. The biggest challenge often lies in mapping business capabilities. This is for many reasons, but perhaps the biggest is that it’s often left to be maintained by an enterprise architecture team. What’s more, it’s often treated as a formality, which means it can quickly become outdated, an unloved PDF somewhere in Google Drive or SharePoint.

In the next section we’ll explore how that challenge can be overcome.

Effective business capability mapping

Mapping business capabilities is most effective with a top down approach. This can frighten some large organizations — it’s complex and time-consuming so it may feel overwhelming. However, this is a hurdle that needs to be overcome: mapping in silos creates duplication and redundancy as you bring the activity together across business units.

The characteristics of a business capability

Before we get into the mapping process, it’s essential all stakeholders are aligned on the definition of a capability:

Business capabilities are the strategic anchor. They drive strategy — not processes or systems. They provide the view needed to make decisions around strategic focus and resource investment. It is not uncommon to find ourselves repeating the ‘What, not How’ mantra several times so that we do not get lost in the details.

Every business capability has a customer. This customer may be external, an internal business unit, or another capability, clarifying its purpose and value exchange.

Business capabilities lend themselves to forming independent teams with clearly defined scope, self-contained processes and systems, and well-defined boundaries and contracts (often exposed via APIs).

Capabilities remain stable even as the underlying technology, processes, or organizational structure changes. They represent long-term business value.

As we go about this exercise, it will be necessary to re-emphasize these principles to avoid confusion between capabilities, processes and systems.

It’s important before initiating anything else to identify stakeholders. They should be drawn from across the business, not just one corner of it, and also situated close to operations, which will allow us to discover more granular capabilities, and provide information on maturity if we need it.

A four-step approach to mapping business capabilities

We see mapping business capabilities as something that requires four key steps:

Set the baseline. Start with standard industry domain models.

Focus capabilities to your context.

Analyze business scenarios and underlying capabilities.

Operationalize by making recommendations that can be fed into the roadmap.

Let’s now look at each of these in more depth.

1. Setting the baseline

A common mistake we’ve seen enterprises make is trying to create everything from scratch. It’s simply not necessary: business capabilities have been around for decades even in our own modern, digital context. Effort has already been put into standardizing most capabilities — trying to organize what are currently perceived as capabilities without having standard definitions in place is counterproductive.

Here are a few industry frameworks and standards we’ve found useful in our work:

Standard Framework |

What is it? |

Further Reading |

| ISO:19440 | This is the International Standards Organisation’s framework for business architecture. |

Link |

| TOGAF | This is a standard based on the Technical Architecture Framework for Information Management (TAFIM). | Link |

| ISO:20022 | This is a multi-part International Standard prepared by ISO Technical Committee TC68 Financial Services. |

Link |

| BIAN | This is a standard from the banking industry based on ISO:20022 that offers great structure and definitions for the various business capabilities we observe in enterprises today, even outside banking. |

Link |

| LeanIX | LeanIX is a common tool to record and maintain business capabilities at enterprises. |

Link |

Most of these frameworks offer a download of standard capabilities with descriptions that can form a solid foundation for a business capability map.

2. Focus

From a baseline based on industry standards, we need to eliminate capabilities out of scope for our particular context. Through interviews and team workshops, we can demarcate the capabilities not used in the company.

3. Analyze

Even at this high level of business capability mapping, it’s possible to derive some actionable insights, depending on how much time and effort we can budget for the exercise. Here are some potential analyses that can be run:

- Tagging business capabilities to service domains/lines of business. Identifying which lines of business depend on each capability is the most obvious investigation that can drive business value. A capability used by multiple lines of business offers two immediate insights: it might be standardized to guarantee consistent, quality experiences to the customers it serves, and, if it’s a common standard capability without much specialization, it might be possible to consolidate across lines of business to save costs.

- Tagging business capabilities to processes. If we’re able to tag existing processes to the capabilities they depend on, we’ll be able to identify what capabilities we need to invest effort in.

- Bucketing capabilities on their purpose. It’s important for any enterprise to have a clear, current view of what purpose each capability serves. It’s crucial to direct investments to the right areas based on fast changing business contexts and environments. Here’s one way to bucket capabilities by purpose:

| Advantage |

|

|---|---|

| Strategic support |

|

| Business necessity |

|

Slicing and dicing capabilities should be much if you’ve standardized language and organizational structure. In turn, we can use these insights to create a further roadmap for investment.

4. Operationalize

We’ve found we’re often given an outdated, forgotten file that contains existing business capabilities — a sure sign that the capability map was actually created, even if it wasn’t put into action. To see the value from this whole exercise, we need to make sure, then, that we put mechanisms in place to connect it to the work our teams are doing on the ground, even if indirectly:

Governance. This is about ensuring accountability around business capabilities and maintaining a capability map to avoid precisely the issues discussed above.

Funding model. We also need to identify areas that require investment, which means we also need a funding model that can provide the necessary resources.

Tooling. Most enterprises face significant hurdles in maintaining the map without a dedicated tool. It’s worth investing in specialist tools such as LeanIX, Arqdoc, BizzDesign, Orbus or HOPEX. Such tools typically make it easier to maintain relationships of capabilities to technology applications, organizational units and business processes. This helps embed the capability map into the operations of the enterprise.

Conclusion

It’s all too easy to lose sight of the value of a clear and well-maintained view of business capabilities. After all, it’s complex and possibly time-consuming — surely there’s a better way to spend time and money?

This is, however, a mistake — a business capability map can not only deliver real business value, it can do so over a sustained period of time. We’ve seen, for instance, how business capability maps can help organizations consolidate redundant processes and technology tools, cutting costs and improving operational efficiency.

What’s more, we’ve found an approach that means large organizations can do this without losing focus on the core of their business. And in times of rapid change and uncertainty, what could be more important than that?

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.