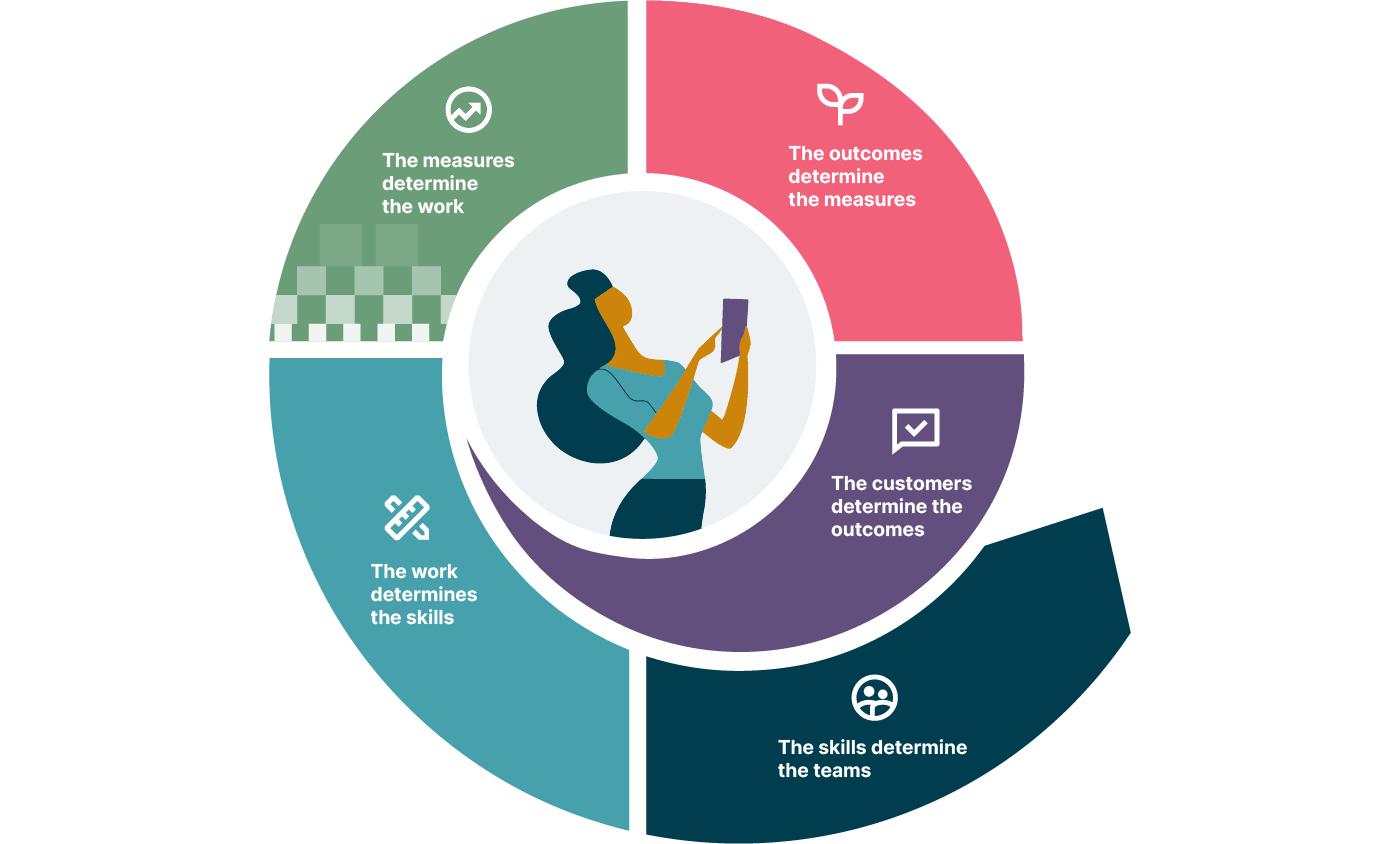

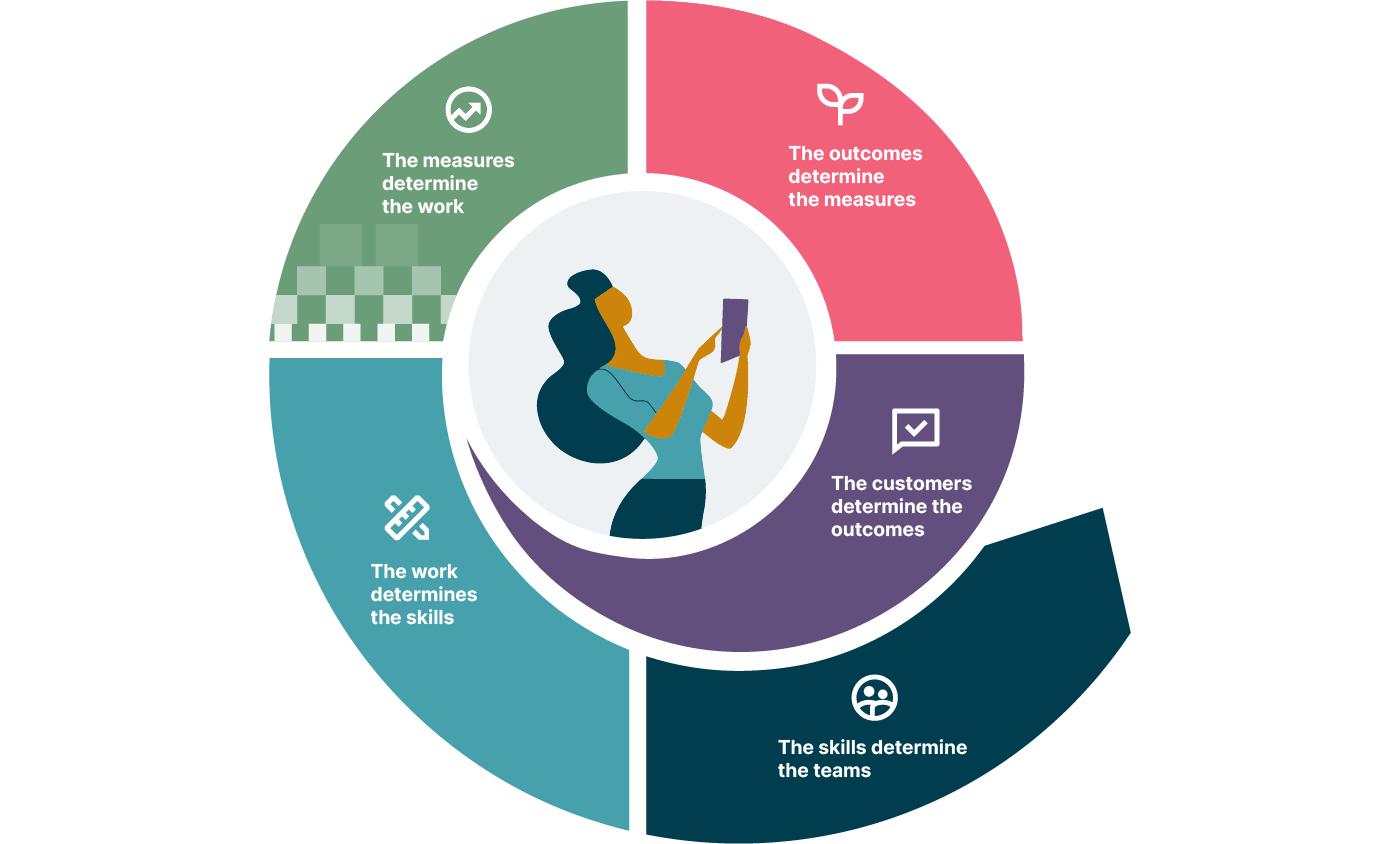

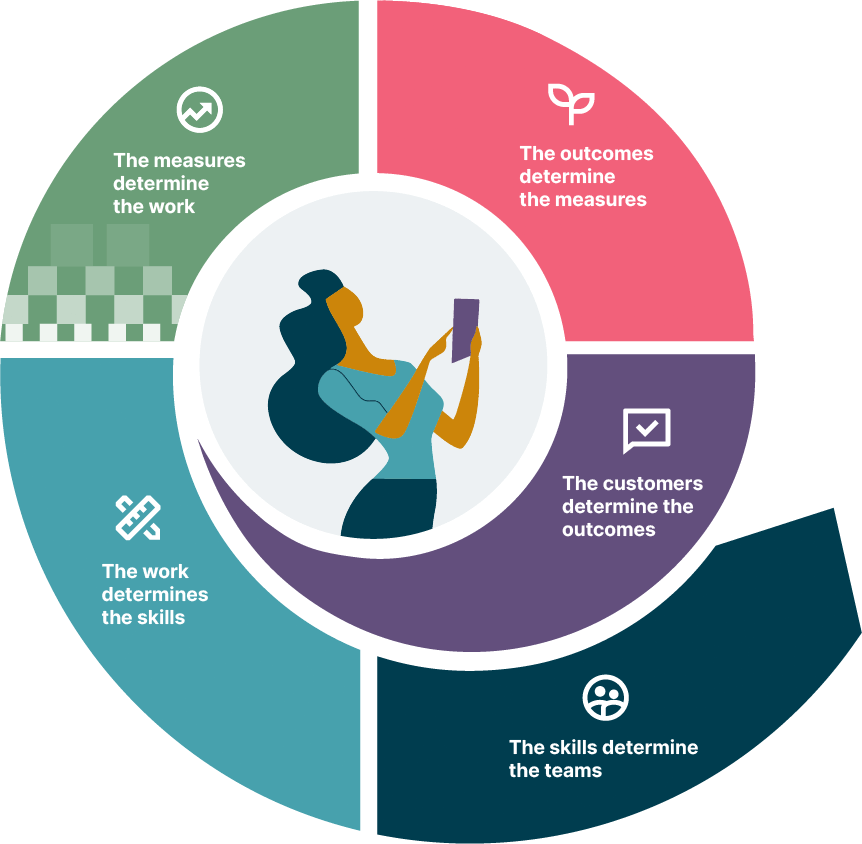

The Thoughtworks Simplified Operating Model starts with the customer. Organizations optimize their operating models to maximize the value they create for customers, rather than designing work based on what their teams can do, and what they want to achieve for the business. Each element builds its own momentum, and allows work to cascade through.

Today's enterprise operating models are no longer fit for purpose. They inhibit change, rather than enable it. They constrain agility, rather than empower adaptation. As a result, too many organizations are hampered in their efforts to survive and thrive in this new digital era – an environment shaped by global disruption, economic uncertainty and rapid technology adoption.

The good news is, there’s a solution. And it’s very simple. However, it will take courage to implement, as it completely overturns entrenched habits, structures and processes.

Let’s start by challenging a longstanding claim that pervades so much research into transformation: depending on who you ask, anywhere between 70% and 97% of transformations fail.

Businesses struggling to meet constantly evolving client and industry expectations may feel somewhat reassured by sensationalist statistics like this. At least they aren’t the only ones failing to make an impact.

But how are we defining failure here? Transformation has no defined endpoint. We all work in an operating state of constant evolution. After all, if transformation can improve efficiencies and provide a competitive edge in the digital age, why would a business ever stop?

It’s time to re-think this mindset – and that means flipping the foundations of our business. We know that an organization’s operating model will determine what that organization is optimized for. It’s the basis of Conway's Law: any organization that designs a system will produce a design structure that copies the organization's communication structure.

In other words, if teams are siloed, outcomes will be too. If the strategy doesn’t align with its execution, there will be friction. Perceived setbacks in the transformation process all stem from unintended consequences of your operating model.

Spotting dysfunctional red flags

Operating models aren’t inherently right or wrong – but they can cause dysfunctional ways of working. Often this is because transformations are tackled as a piecemeal project, without taking into account how the organization broadly delivers value. You can plant the seeds, but unless you adapt your operating model to their growth, how will new ideas take root and flourish?

Here are five dysfunctional states we often encounter at Thoughtworks when clients bring us in to review their transformation initiatives. You may find yourself nodding along in recognition of all of these, because one inevitably leads to the next.

1. Outcomes are created internally

When objectives are set from an inside perspective, they tend to fulfil self-serving beliefs. And that means they are disconnected from customer value and purpose.

Outcomes should be the starting point for any project. If they’re off-center, everything will be impacted. If you prioritize the company over the customer, what you measure and value will fail to align with what should be your ultimate goal – making things better for customers.

For example, a bank might set an internal outcome of ‘selling more home loans’. They’ll set some KPIs around mortgage growth, and perhaps they might build an MVP for some sort of digital mortgage platform.

But what if they optimized their model to what customers are looking for instead? No one really wants a mortgage – but they do want a place to call home. Instead of asking themselves how they can sell more mortgages, they should be asking how they can help more people buy their home.

This triggers an immediate shift in empathy. And the team might start thinking more about home affordability, simplifying the search, purchase and approval experience and what it takes to move. And the things they measure, the skills they need on the team and the resulting MVP will all be completely different.

2. Measures are created after the work is decided

Too often, organizations fall into the well-worn habit of measuring things they are used to counting – typically financial metrics. Someone (let’s say the CFO) has decided it’s time to cut costs or grow revenue, and sets that measure – even though it has no correlation to the intended outcome.

If you are measuring what you can count, rather than the customer-focused outcome you’ve set, you won’t know if you have achieved it. And you won’t be able to spot opportunities to adapt if you see a better way to achieve that outcome, scale the project if it succeeds or stop work if it is clearly not on target.

Ideally, your measures should be a lead indicator of the lagging outcome measure. For example, imagine what would happen if the Department of Immigration measured how many people settle in Australia, instead of how many visas are issued? Every part of the experience, from initial assessment to support services might then be seen through a different lens.

3. The work is determined based on current skill sets

There is a bias towards starting work because it’s the type of work a team can do – often because we want to keep people busy. But if it’s the wrong type of work for the outcome and measures above, you are just setting your team up for failure.

This state is typically thanks to an operating model that thinks functionally and is designed for utilization, rather than outcomes. Ultimately, it constrains progress on ideas.

This starts with aligning work to the desired outcome and measures. We often see programs of work broken up into functionally-aligned pieces, and then sent to function teams for completion. These teams lose sight of the work’s ‘why’, because they lack that shared context.

A backlog of work for a specific application or a defined skillset like CX, bears no resemblance to a backlog of work for helping people find their dream home or settling immigrants into Australia. There will be significant differences between the things you measure, the skills you need, and the work you create.

When people can see why they are doing the work, how it links to purpose and outcomes and how they will measure success, they will know when to pivot, when to accelerate and how to use their best talents to achieve the outcome.

4. The skills don’t match the high-value work required

There’s no doubt recruitment and development teams are under pressure right now, given the chronic and growing tech talent shortage. To solve this, they’re going to have to exercise a different kind of skill acquisition muscle – stop hiring role replacements, and start thinking about what really suits the organization’s future work.

If the skills within your organization fail to evolve at the same pace as the shifts in market opportunities, you’ll fall behind. It’s one of the biggest causes of organizational model friction. And what happens is we enter a skill-dysfunctional state: we hire to optimize a department’s function (because someone just left and we have budget) instead of optimizing for the outcome we want. That means we can’t do the work that is most likely going to achieve that outcome.

Imagine you could start your business again with a clean slate, and design the workflow based on your customer-first outcomes and measures. I would guess you’d have at least a 40% gap in terms of your current skill set mix – with many of the ideal skills reporting to the wrong person or business lines.

This means HR has to constantly shapeshift the organizational structure around skills, not functional units. To continually look ahead to what skills need to be developed internally or brought into the business, they will need to be across the program of work, measures and outcomes.

5. Teams are created functionally

Finally, this misalignment of skills tends to see organizations optimize teams for their skill set along reporting lines, led by a manager who has tenure and expertise in that function.

And that just makes it harder to get things done.

It happens because we are still driven by budgets and traditional organizational structures. In this state, transformation work has to be disseminated across the business just to be completed, resulting in clunky workflow and roadblocks. Those small pieces of work are rarely tied back together, because teams working on the same outcome are siloed and likely don't even know their work is connected.

It’s the opposite of an agile empowered team aligned around a common purpose and outcome. And it costs your organization money – and results in large program management overhead.

Again, this stems from a self-preservation bias to maintain the skills we have, and ensure they are valued. A team full of cloud experts will strive to ensure the latest cloud tech is used – regardless of whether it is the right solution for the outcome.

So how do you know if your model is falling into any of these traps? Start by asking yourself these questions:

How much of our work is born from a defined outcome? Are we simply relabelling the same work?

How much work has to leave the team to be completed? Teams should be autonomous and aligned to the work.

How much work has been stopped or adapted based on new knowledge? We need to know we are willing to learn and have the courage to act on what we find, even if it means uncomfortable decisions.

A radically simple operating model

It’s one thing to identify dysfunctional areas that could be holding you back, and another to turn your operating model on its head. But that’s exactly what you need to do.

Over the years, Thoughtworks has developed a simplified operating model that starts with the customer. Each element builds its own momentum, and allows work to cascade through.

Everything starts with the customer. The outcomes you set for the business strategy must be driven by a customer need. Then, that outcome determines the measure you put in place - so you are measuring the right things to know if you are succeeding.

Once you know those measures, you can design the right work to achieve them. Then you will know what skills you need to complete that work – and what the team structures should look like.

In short, when teams are aligned with the value of their work, and can complete their work within the team, it’s easier to measure the impact – and achieving the outcome is the prime objective.

It seems obvious, yet I’d estimate 90% of organizations are still designing work based on what their teams can do, and what they want to achieve for the business. Yet if you optimize your operating models to maximize the value you create for customers, the outcome will be profitable growth – along with the ability to adapt and evolve in changing markets.

The Thoughtworks Simplified Operating Model

Customers determine the outcomes

Outcomes determine the measures

Measures determine the work

The work determines the skills

The skills determine the teams

Given the current market uncertainty, there has never been a better or more critical time to tackle this dysfunction. And it gives you the ideal platform to identify potential cost savings, focus on high-value investments, and adapt quickly to defend against emerging threats or make the most of new opportunities.

If you’ve been looking for one thing you can do to become a more resilient evolutionary organization, this is it. You’ll achieve what you optimize for – so choose wisely.