4 Significant Ways to Improve Your Ability to Innovate

Liberate teams from the annual budget cycle

The use of the traditional annual fiscal cycle to determine resource allocation encourages a culture that thwarts our ability to experiment and innovate. It perpetuates spending on wasteful activities and ideas that are unlikely to deliver value. How can we get out of the rut that is the annual budget process and encourage experimentation and innovation within our organization?

When it comes to budgets, It is hard to let go of the long-held belief that strong, centralized control provides valuable efficiencies. However well it may have served us in an era of lower complexity and slower technical advances, it now creates barriers that prevent us from adapting quickly to emerging opportunities. In this context, the resources and efforts required to gather information, communicate, and monitor rigid centralized processes outweigh any efficiencies gained. As well, a strongly controlled centralized budget process encourages competitive, rather than collaborative, internal behavior. This is counter-productive to innovation, which requires teamwork and collaboration across the organization.

Three mistakes of budgeting process

There are three common mistakes that retard experimentation and innovation in the use of technology in the traditional centralized annual budget processes..

- Basing business decisions on a centralized annual budget cycle, with exceptions considered only under extreme circumstances. This combines forecasting, planning, and monitoring into a single centralized process, performed once a year, which results in suboptimal output from each of these important activities.

- Using the capability to hit budget targets as a key indicators of performance for individuals, teams, and the organization as a whole, which merely tells you how well people play the process but not the outcomes they have achieved over the past year.

- Basing business decisions on the financial reporting structure of capital versus operating expense. This limits the ability to innovate by starting with a minimal viable product that grows gradually or can be discarded at any time. The CapEx/OpEx model of reporting costs is largely based on physical assets and is project based; it does not translate well to the use of information to experiment, learn, and continually improve products over time.

Don’t get me wrong, having a budget is a good thing, especially when we set some stretch financial targets for ourselves. Financial constraints can be a strong catalyst for creativity, collaboration, and innovation. Particularly in the explore domain of product development as described in Lean Enterprise, we can spur innovation if we purposefully reduce funding to localized areas or products and allow teams to decide how they can best utilize available funds, However, this approach will not work if we simply reduce funding and tell teams what their targets are and how to achieve them.

An alternative — rolling forecasts

Rolling forecasts is one tool that can be useful to help improve financial planning and decrease dependency on the budget. As every period is completed, another is appended to the far end of the forecast so that it always covers the same length of time into the future. The far end doesn’t provide great detail, but does include known cost line items with estimates on what they will be for the period in question. In rolling forecasts, attention is focused on the near future, based on current and accurate information. We don’t spend as much time chasing details further out into the future that are likely to change in an unknown way.

In adopting this approach, remember that the forecasts are not meant to define targets or manage resources. Unless you use an approach such as strategy deployment or Ambition to Action to set targets and manage resources and performance, as described by Bjarte Bogsnes, you will end up with a rolling budget instead of rolling forecasts, which Bogsnes describes as “a bit more dynamic but also four times more work.”1

As we separate activities required to perform good financial management from the annual budget process, we improve our ability to understand our current condition. We focus on developing flow in decisions and adjustments required to meet the targets we have set for ourselves. The shift is from “Do I have the funding to do what I am told to do?” to “Is this really necessary?”

Dynamic resource allocation reduces risk

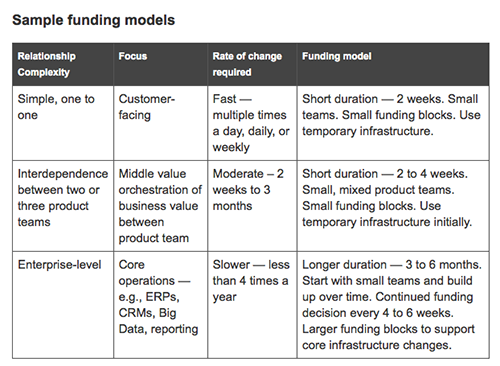

Some companies are taking an approach known as dynamic resource allocation to control costs and aid funding decision making for technology innovation. It creates more frequent checkpoints for funding decisions, and each decision has less risk associated with it because the amount in the funding blocks is much smaller. All decisions are based on the empirical evidence demonstrated through working software, so they become easier to make. When done correctly, access to funding expands to more teams, is more frequent, has less associated risks, and brings better results. We thus encourage more innovation and reduce financial risks associated with large initiatives.

The product development model discussed in Lean Enterprise works well with dynamic resource allocation. When we have a new idea, we must begin with an explore phase. The cost of exploring the idea can be measured in terms of the product team’s operating costs. Boundaries are defined: you can have a small team for a defined period, and the maximum amount to spend is X. Once the team has evidence the idea will deliver value, we can provide further funding to move into the exploit domain. Our goal is to invest limited resources in a number of possible options, with the expectation that most will fail but a few will present great opportunity.

Teams that successfully exit the explore domain and scale up will begin to practice continuous improvement to constantly remove waste in the delivery process. It’s essential to avoid “rewarding” teams that achieve performance improvements by reducing their operating costs, cutting team size, or breaking teams apart. This instantly demotivates teams and kills the innovation mindset. Instead, the team should get to spend more time on exploring new ideas without onerous documentation, reviews, and approvals — as long as they maintain their high performance and keep costs within established boundaries. By creating lightweight processes to approve small blocks of additional funding to support the exploitation of ideas, we keep the momentum going.

Track products or services, not projects and operational line items

By using a product paradigm rather than a project paradigm, it becomes much easier to calculate profit and loss on a per-product or per-service basis. We can calculate the costs of delivering and running a product or service simply through the costs of the team building and running it. This makes it much easier to see when the costs associated with a product or service exceed the value it provides, or when we are not obtaining the expected margin.

As the value proposition and development and support costs of a product change over its lifecycle, we can change the composition of the team running and enhancing it. Finally, when the product starts delivering a negative value, we should retire it — sooner rather than later. This can require buy-in from executives: we know of one Fortune 500 company that gave bonuses to its VPs based on the number of services retired during the year, aiming to reduce system complexity and encourage innovation.

Be flexible and apply control at the right level

Smaller, simpler, local initiatives involving less risk should go through less review and a lighter approval process than complex, enterprise-level initiatives. Hand-in-hand with this, we need an ongoing process and defined criteria for when funding will cease. Review and oversight can be decentralized by creating local teams responsible for reporting the outcomes of their funding decisions. This can be rolled up for enterprise-level reporting. We still want to maintain high-level centralized control over larger enterprise initiatives, but there should be very few of these at any point in time.

Getting rid of a highly centralized annual budget cycle does not mean we are shirking our responsibilities for good financial management. Start by decentralizing financial responsibility for operations and moving it down to individual business units:

- Senior management doesn’t set the targets for all costs and revenues for the upcoming fiscal year.

- Critical business decisions are based on what is good for the business, not on a line and number in the budget doc.

- Teams and individuals are measured by their ability to perform and produce value, not on their ability to stay within budget. Everyone still has targets and is held responsible for improving the value they deliver. However, these targets are not mandated from the top but set by teams themselves, aligned with the organization-level goals and targets.

Organizations that continue to structure funding decisions around financial cycles will face serious obstacles to improving their innovation capabilities. We need to move beyond the centralized budget paradigm and introduce flow into the processes of financial forecasting, planning, and reporting. Disassociate funding decisions from the annual budget cycle, and stop doling out funds based on capital or operational expense buckets. This is how we can make better decisions on what and when to fund and create the outcomes we want.

Many large multinational organizations have transformed themselves by dropping the long-held belief that command and control is the best way to manage their financial processes. This article provides you with food for thought and I encourage you to do further reading on this topic. I recommend Beyond Budgeting (Hope & Fraser 2003, Harvard Business School Press) and Implementing Beyond Budgeting (Bogsnes 2009, John Wiley & Sons) as well as the Beyond Budgeting Round Table website.

- Personal correspondence

A version of this article first appeared in O'Reilly's Radar.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.