I first attended a retrospective 15 years back at Thoughtworks. The facilitator was the legend himself, Pat Kua. I worked with Pat for a few months and each retrospective he facilitated was a masterclass. Much of what I’ve learned in subsequent years builds on the foundations of what I learned by observing Pat. In recent years, I’ve spent some time building retrospective kits on Mural for teams to facilitate retros for themselves. These kits help new facilitators work with a predictable, sometimes formulaic, plan. To me, retrospectives are one of Agile’s key mechanisms for continuous improvement and self-healing. Teams should do these often — if possible, every sprint.

That said, the real world often diverges from the ideal. Many teams don’t conduct retrospectives for months. This leads to a backlog of ideas that the team can’t release quickly enough. So when they do retrospect, there’s a deluge of contribution and a major part of the meeting is spent just collecting and synthesising these inputs. You can use hard time boxes to keep the meeting moving, but after a certain point, it can feel like you’re only keeping time and not achieving the aim of the meeting.

That’s not the only problem with irregular retrospectives. Without a ritualistic forum to share their ideas, team members can feel uncertain about whether ideas are really welcome. That, in turn, lowers the sense of safety and openness for people — a prerequisite for effective retros.

I recently facilitated a retro for a team of 18 people (a large one by agile standards) distributed across the world — Australia to North America. The team had done no retrospective meetings for the last year. As the last few paragraphs may have shown, this sent my spider sense tingling. In this post, I want to show you how I organized and facilitated this retrospective and how to handle such a situation if you ever face it yourself.

Making the most of the time available

The first challenge, as I mentioned, is making the most of the time available. If a team hasn’t retrospected for a while, you might find that anything short of 90 minutes is too short. If the team is large, as it was in my case, you need more time. Moreover, when a team hasn’t retrospected for very long, people need time to think and reflect. Synchronous collaboration is rather intense for this kind of quiet reflection. So it makes sense to have people share all their inputs asynchronously.

To make this happen, I set up a Google form. I had planned to run the retrospective in a starfish format. It’s a format that allows teams to think beyond black and white categorisations, such as “what went well” or “what didn’t go so well” . The questions in the form were all to that effect. To help the sense of safety, I kept the form anonymous. There’s a tendency for people to disregard forms and surveys, so I put a few nudges in place to ensure that everyone takes the time to reflect and add their thoughts to the retrospective.

- I emailed everyone individually, introducing myself as the retro-facilitator and requested them to fill out the form. People pay more attention to a one-to-one email than one that’s addressed to a mailing list.

- I also blocked time in everyone’s individual calendars, at a time that worked for them in particular, so they had a ‘default’ time carved out to do this.

- Third, I asked the members of the team who’d requested me to facilitate, to send a few reminders on the team’s chat group and mailing list, so they knew they had to pay attention to the form.

Improvement with acknowledgement

An anti-pattern I’ve observed in retrospectives is the tendency to focus only on the things that need improvement. While the starfish is a great pattern to add balance to a retrospective, it’s not meant for celebrating and acknowledging our team mates. This team hadn’t reflected on their time together before this, so I wanted them to have a space to say thanks to anyone who enriched their experience at work. I got these inputs through a question like the one you see below.

Why use a form?

One option to get inputs asynchronously is, of course, to get people to contribute directly onto the collaborative whiteboard — in this case, Mural. I have had little success getting people to contribute their thoughts in advance with just these whiteboards. Only a few people spend the time to add thoughts asynchronously using these tools. I don’t have a very well formed opinion about why this happens, but here are a couple of potential explanations:

People rarely associate whiteboards with asynchronous collaboration. The mental switch needed to change their behavior vis-à-vis these tools may be a bit too much for most people.

When reflecting asynchronously through a form, people can choose to focus on one question at a time. The whiteboard comes with too much cognitive load. Zooming into a specific question feels like one extra step that adds friction.

While you can technically turn on ‘Private mode’ indefinitely, people don’t immediately feel a sense of anonymity when they contribute directly onto the whiteboard. This often leads to another level of friction. The design of survey forms allows for anonymity to be an obvious feature.

Of course, that hypothesis might be wrong! Forms are not perfect by the way, but I’ve used them more often for asynchronous inputs, with greater success. In fact, for this retro, all participants responded to the survey, and well in time. That’s as good as it gets!

Setting up the retrospective environment

As I mentioned earlier in this post, I’ve been working on kits to help teams run their retros. This was a great opportunity to eat my own dog food. So I used the starfish retro kit you see above to layout the environment for the retrospective. It has a bunch of familiar sections that are common across all the kits I’ve created.

Safety check.

Brainstorm.

Actions.

Kudos.

Each section has instructions embedded, so that even if you’re a skilled facilitator, the group you’re facilitating has another way of knowing exactly what’s happening. This group had also asked for an energiser during the retro, so I added one to the kit after the fact. Now, be mindful of the fact that I picked Mural as the collaborative whiteboard. You should pick what your group is familiar with and make sure you set aside a few minutes to onboard people to the tool.

Collecting inputs with the final medium in mind

A challenge when collecting inputs on forms is that people forget that their inputs eventually need to go on sticky notes. They need to be brief. To pre-empt verbose inputs, I added some instructions on the form, and then repeated the following line on every page of the form.

“One line for each point, ≤ 100 characters per line.”

Doing this helped ensure that transferring inputs from the form to the mural canvas was just a straightforward copy-paste job, where all inputs easily translated into sticky notes.

The safety check

When teams haven’t retrospected often, you can’t take safety for granted. In such situations, a safety check becomes necessary. The easiest safety check is an anonymous poll on a five point scale where five represents the highest level of safety

I’m not going to talk at all, I don’t feel safe.

I’m not going to say much; I’ll let others bring up issues.

I’ll talk about some things, but others will be hard to say.

I’ll talk about almost anything; a few things might be hard.

No problem, I’ll talk about anything.

Theoretically, if a team’s safety isn’t high, you don’t retrospect on that day and instead consider how we can address safety. This is tricky. If people aren’t feeling safe, you can’t obviously ask them to voice out aloud why they feel that way. So the brainstorm itself needs to be anonymous. There’s also the notion of a tipping point. How many ones and twos on a safety check are too many? These are judgement calls we need to take as facilitators.

Coming back to my team of 18, the retrospective was fairly high stakes. Let me explain. This was a global team, working across time zones. Wrangling a two-hour slot on their calendars was a feat in itself. Postponing the retrospective could have meant not doing this again for weeks. So when I ran the safety check and saw an uncomfortable number of ones and twos, I had to improve the safety of the group during the retrospective itself. I asked the group a question and solicited anonymous responses to it.

“How can we improve the sense of safety in this group so everyone feels comfortable to speak up?”

The responses I got were well within my control as a facilitator.

Make inputs anonymous.

Share 1:1 notes with the facilitator.

Ground rules:

“no judgement”;

“discuss thoughts without undue attention to who wrote them”

Your situation may vary, but you can still apply the above method to determine what’s behind people’s low perception of safety. In my case, all I did was reiterate the prime directive and assure the group that they could contribute their thoughts to the retrospective anonymously. If I needed them to write sticky notes, then I’d do this using Mural’s ‘Private mode’. And if there was a discussion they wanted to contribute to anonymously, they could just send me a one-to-one chat message. With those assurances in place, we re-ran the safety check. In this second run, the ones and twos had shifted to threes and fours. We acknowledged that some people felt less safe than the others and the rest of the retro proceeded with that sense of empathy.

Follow up - actions and backlog

The rest of the retro was as you’d expect. Voting, prioritisation, discussion, action items - all the good stuff. We identified owners for each of the actions and could cover five major topics of interest to the group. We even looked at all the kudos the group had shared with each other to celebrate the team. As a follow up, I wanted to ensure that the team doesn’t forget about the topics that they didn’t get time to discuss. So as a follow up, I exported items from the whiteboard into a two tab spreadsheet.

Tab 1 - Actions; with the following fields:

Description

Owner

Why (the trigger for the action)

Next steps

Tab 2 - Retro backlog; with these fields:

Item

Area (of the retrospective starfish)

Number of votes received

My aim is to provide a nudge for the team to track not just the prioritised actions, but also their retro backlog. That way, continuous improvement can become a part of their way of working.

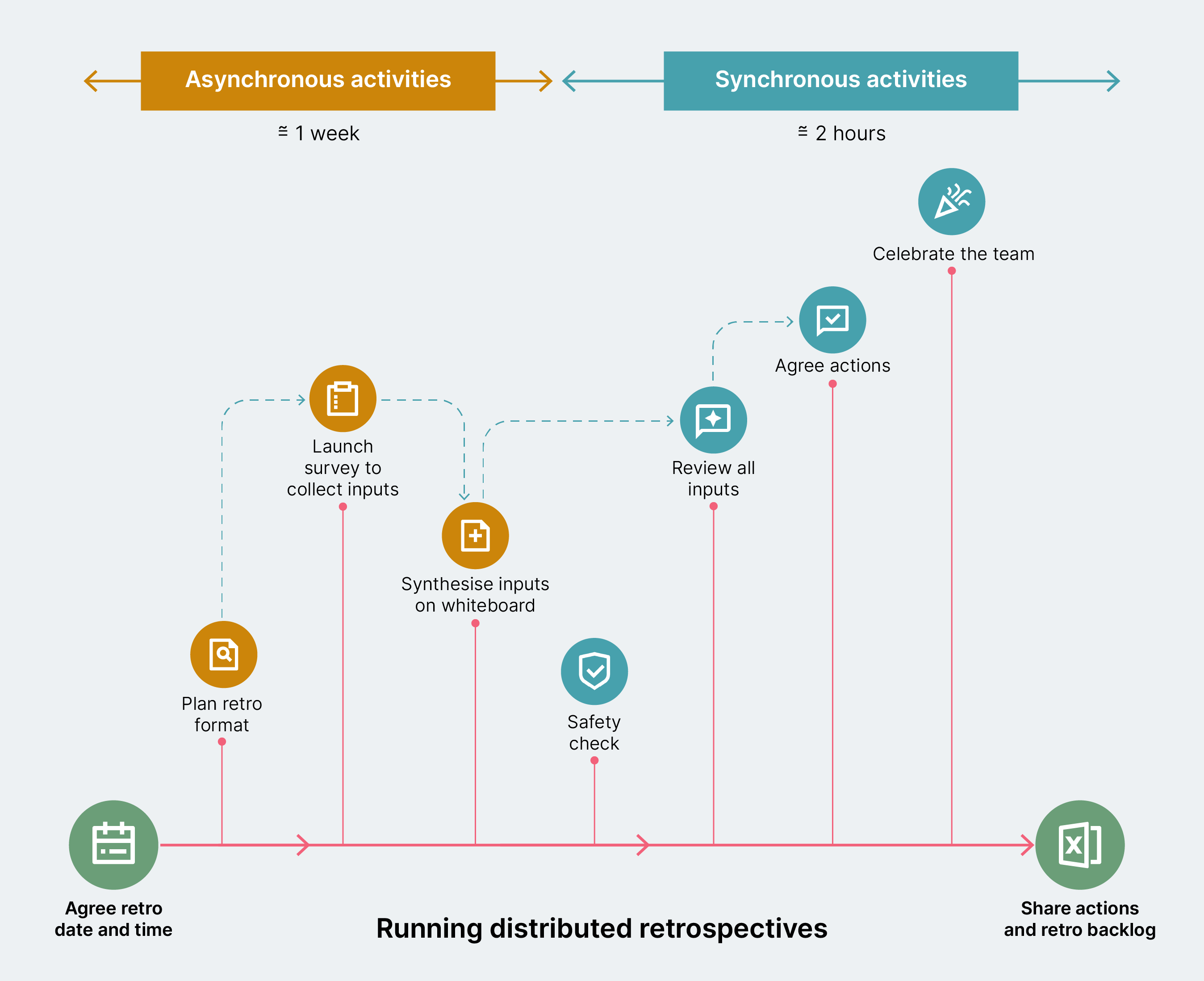

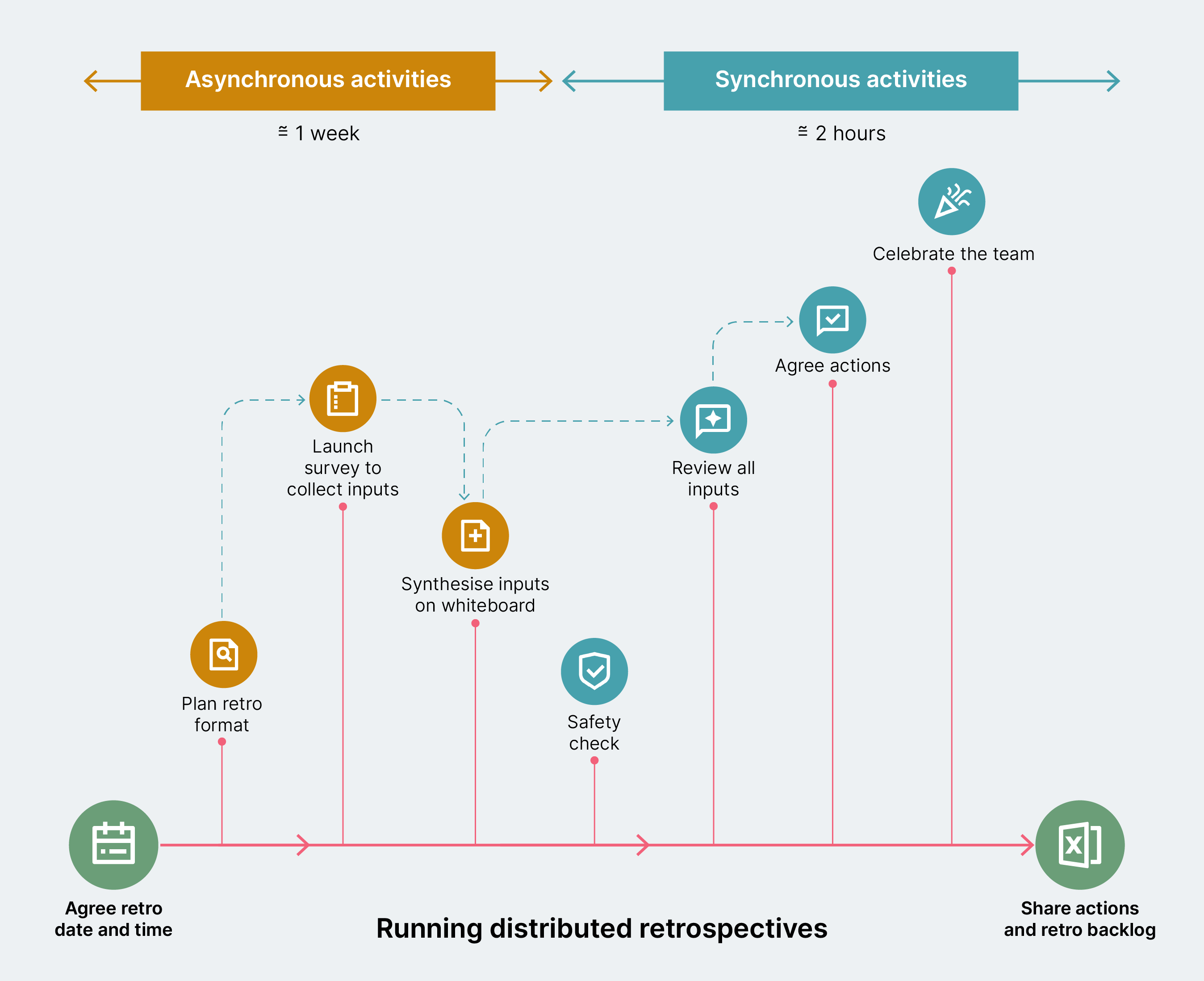

The diagram you see above maps out the approach I’ve described in this article. It should help you adapt my ideas to your own context. When we do them regularly, retrospectives can be short, fun and free of undue ceremony. Most teams should aim to get to that level of maturity as they form, storm, norm and eventually perform. In fact, with some discipline, retrospectives may not always need to be meetings, as some asynchronous first practitioners may tell you. The trouble is in trying to get to this stage before your team’s ready. In teams where these rituals are infrequent, facilitators need to tread with care. I hope this article gives you a flavor of the techniques you can employ to create an inclusive and productive environment in retrospectives; especially with teams that don’t do them often. Also, I hope the recipe I’ve outlined here is repeatable enough that you can do retros more often and more effectively than you do today.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.