"Software development effectiveness” has recently become an industry buzzword, frequently featuring in conferences, mentioned by tech giants and teams pursuing higher efficiency, such as Alibaba’s effectiveness 211 vision, Tencent's intelligent development platform and Baidu’s engineering capability white paper. But the question of what constitutes an appropriate effectiveness metric still remains. The “lines of code” metric used a decade ago is no longer applicable to the understanding of software development in the modern agile process, which has left the software industry of today with no unified or widely recognized method for measuring development effectiveness.

What are the appropriate software development effectiveness metrics?

The question of what appropriate metrics are first requires figuring out what data to measure. Different metrics have been proposed depending on different concerns, but according to our own personal experience, the current commonly used metrics can be categorized as follows:

Planning progress: assessing progress, obtaining background information and context, knowing when the task is completed, predicting the problem (future), and replaying and reviewing the problem (past).

Burn down chart (sprint/release)

Velocity chart

Standard deviation

Throughput

Cumulative flow diagram

Control chart

Kanban WIP board

Fast feedback: continuous integration, continuous deployment.

Build and deploy speed

Test speed

PR (pull request) approval time

Unit tests passed

Integration tests passed

Team transformation: using specific metrics to measure different ways of working can influence people’s behavior, for example by making it clear to management that something is unreasonable and needs to be changed or that more time and budget are needed.

Pairing time

Time spent manual testing

PR (pull request) approval time

Fix red build time

Cost of fixing bugs in Dev/Prod

Test coverage

Effort allocation (New work / Unplanned work or rework / Other work)

Assisted decision-making: experiments can be conducted and new metrics can be constantly searched to help make decisions.

Lead time

Number of bugs released (number of escaped bugs)

Effort allocation (New work / Unplanned work or rework / Other work)

Value delivered

Engineering capability: 4 key metrics measure and identify weaknesses in the team’s engineering practices.

Lead time for changes

Deployment frequency

Change failure rate

Mean time to restore

However, it's important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all template. You need to analyze multiple factors to find the metrics that are best suited for your team and continue to modify and iterate on them based on value delivery. Having completely different metrics between teams is normal, as the measurement of development effectiveness largely depends on the type, scale, culture, projects etc.

Faced with the multiplicity of metrics and tool chains, front-line developers might ask: Do I need to put these things into practice? What is my priority at this stage? In the next section, we’ll look at a potential solution to quickly select appropriate metrics and discuss how to calculate the start of lead time when the front business is uncertain (fuzzy front end).

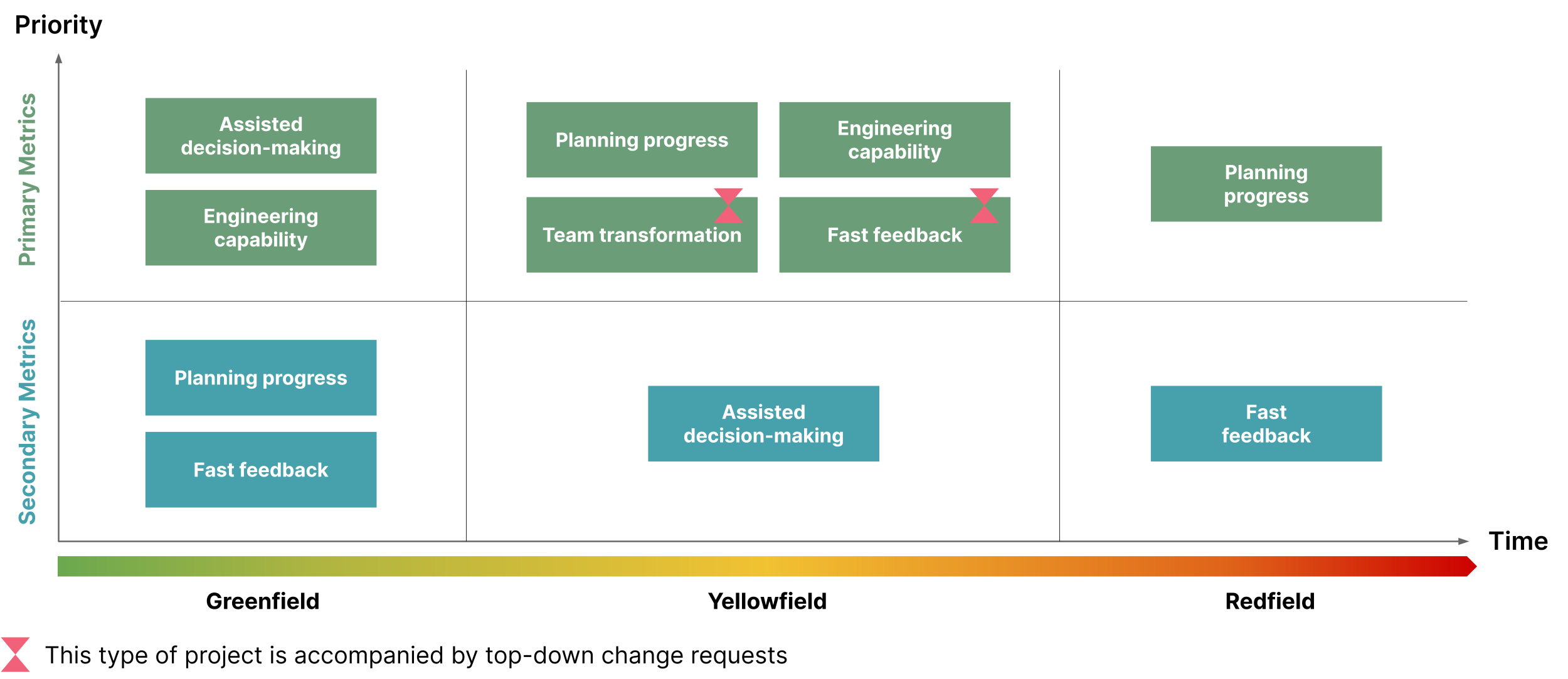

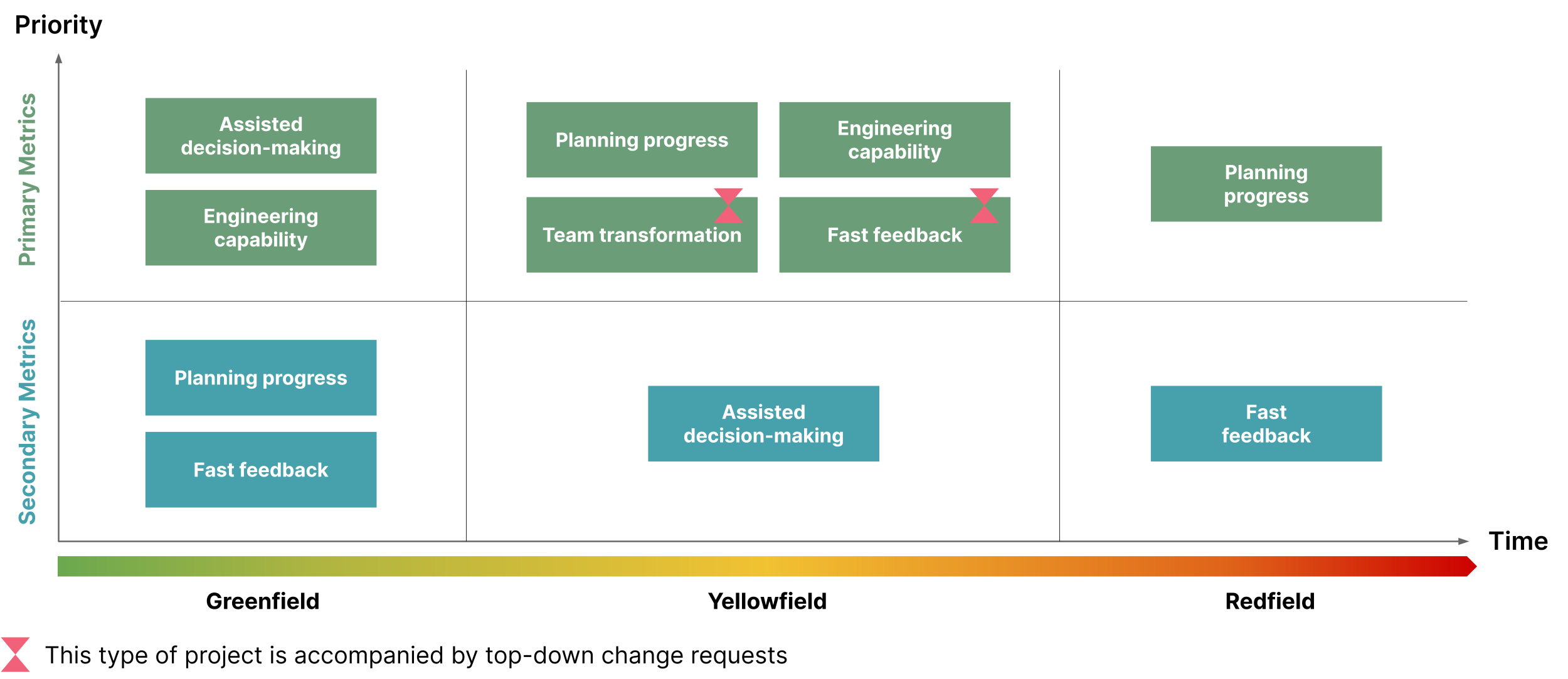

Recommended metrics for three project types

In the software development process, there are generally three phases/types of projects: greenfield, yellowfield (or brownfield) and redfield projects, mirroring the lifecycle of a software system. Identifying the project type can be a quick and efficient solution to finding suitable metrics.

Greenfield: "developing a system for a totally new environment, without concern for integrating with other systems, especially not legacy systems. Such projects are deemed higher risk, as they are often for new infrastructure, new customers, and even new owners." As the greenfield project development team is the most likely to be close to the project's end user, meaning more likely to be carrying out end-to-end measurement, and lacks “historical baggage,” the architecture design and technology stack can be carried out normally. Assisted decision-making and engineering capabilities can be selected as the primary indicators, focusing on the end-to-end value stream while ensuring that good engineering practices are implemented at the beginning of the project. Planning progress and Fast feedback can be used as secondary indicators to assist with end-to-end value flow measurement. Primary indicators and secondary indicators generally affect and confirm each other, meaning that improvements in secondary indicators will lead to improvements in primary indicators (e.g. quick feedback-PR (pull request) approval time improvement results in improvement in assisted decision-lead time). The fuzzy front end can be defined as the moment when the end user puts forward a certain requirement to the team, while the moment when the user requirement is clearly recorded can be regarded as the beginning of lead time.

Yellowfield: "new software must take into account and coexist with live software already in situ.” For such projects, planning progress and engineering capability can be selected as the primary indicators. Improving engineering capability speeds up delivery. Assisted decision-making can be used as a secondary indicator to expand the measurement of value generated by function delivery and promote end-to-end value flow measurement. The measurement of sustainable expansion can also drive the efficiency of the value stream. The fuzzy front end at this time can be defined as the moment business is handed over to development and the story card is clearly defined. Based on past experience, taking over such projects usually requires extensive coordination and communication work as they might be suffering from “the Silo Effect.” At the same time, this type of project is accompanied by top-down change requests (especially for best-selling, long-life cycle product projects). At this time, team transformation and fast feedback can be added as primary metrics to assist with the change requests.

Redfield: The software system has entered the maintenance period; no new functions will be developed, only bugs discovered by end users are to be fixed. After a period of maintenance, it may be replaced entirely by a new system. For these projects, planning process can be selected as the primary indicator to ensure a good bug repair throughput. If the product team wants to increase the deployment frequency and speed up their response to end users’ bug reports, they can choose fast feedback as a secondary indicator. Fuzzy front end can be defined as the moment when the end user clearly reports the bug to the customer service staff.

Factors for rapid differentiation of greenfield and yellowfield: whether the integration and coexistence of legacy systems needs to be considered. Quick identification factors of yellowfield and redfield: whether the system is in maintenance mode only or not.

Greenfield: Developing a system for a totally new environment, without concern for integrating with other systems, especially not legacy systems.

Yellowfield: New software must take into account and coexist with live software already in situ.

Redfield: The software system has entered the maintenance period; no new functions will be developed, only bugs discovered by end users are to be fixed.

The selection of indicators is strongly related to the context of the team. It is necessary to select the recommended indicator set according to the specific context of the team, and tailor the specific indicators in the indicator set.

Measurement debt and governance

As measurement progresses, and development moves from green to yellow or from yellow to red, you may get an ‘aha’ moment: if measurement isn’t done during the greenfield phase, you may incur measurement debt when you move to the yellow or redfield phases. The longer the delay, the higher the cost (or interest) of initial measurement. These are the same concepts of debt and interest involved in technical debt.

For example, imagine a system that analyzes and counts the time spent in each stage of a request to optimize it. If you didn't want to meet the initial cost of measurement requirements, not creating TraceID, Tag or other attributes so that it can follow the request through various systems, then you might find that you can't measure time during the middle of the process. When you try to add the necessary information to make it possible, you'll find that too many systems are involved, some of which you might not even know, and that the workload is too large. It’s similar for debt measurement: in the long term, setting up the necessary attributes during the greenfield stage is easier and more cost-effective than doing it in later stages, at which point it might not even be possible.

How to manage measurement debt?

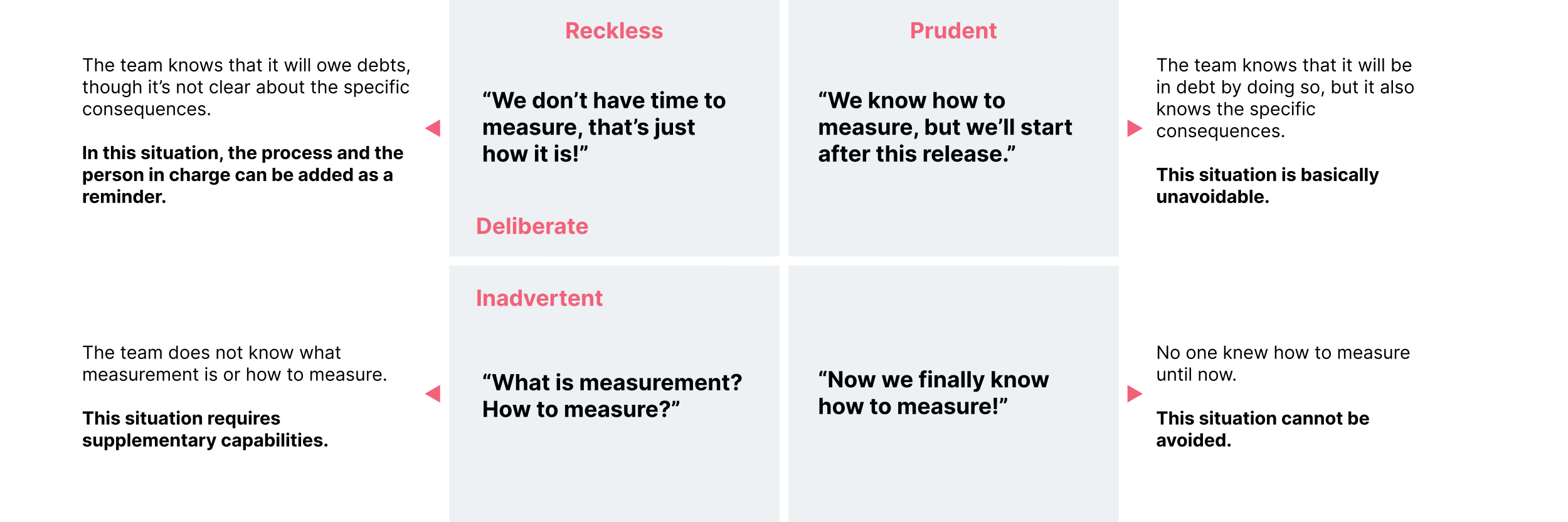

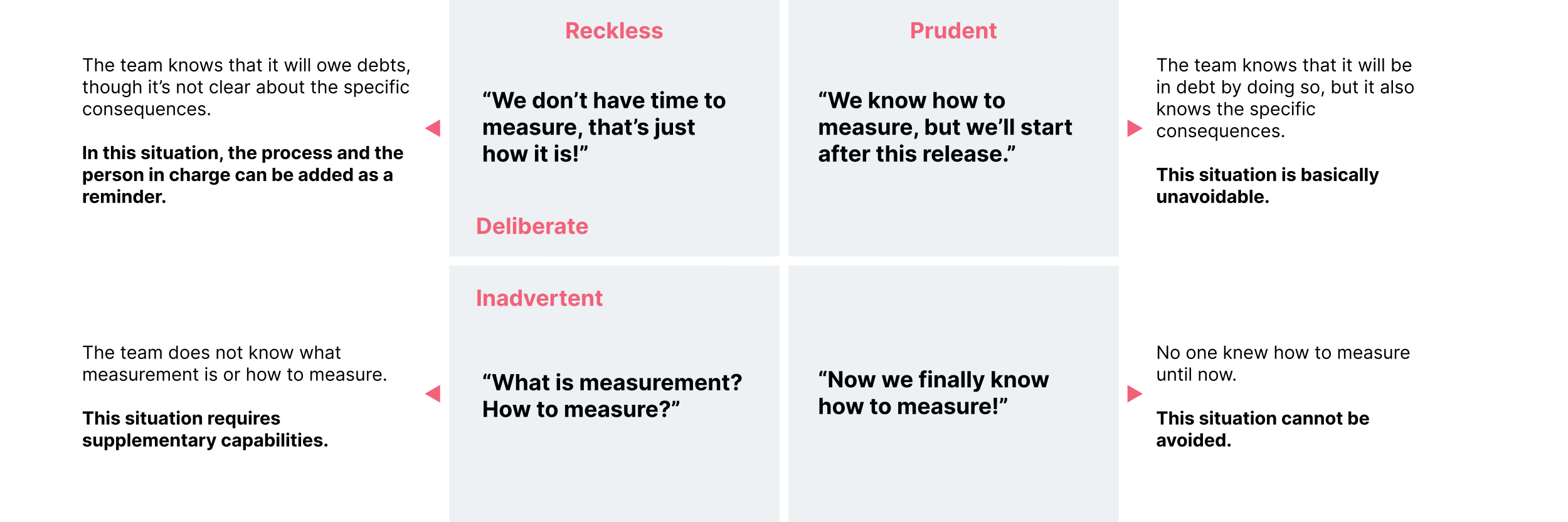

Measurement debt is similar enough to technical debt that we can learn from Martin Fowler’s Tech Debt Quadrant and apply the same terms to measurement debt: reckless, prudent, deliberate and inadvertent.

When you suggest to the team “let’s measure development performance and see if there is anything that can be improved,” you may get the following answers:

Unlike with real-life debt, some kinds of measurement debt are simply unavoidable, which makes it even more crucial to ensure the proper metrics are implemented early on.

In the absence of a universal metric, finding a way to measure development effectiveness relies on analyzing your team’s process and the type of project you’re working on. Metrics might vary wildly between teams, but what all teams should strive for is early implementation of those metrics to avoid incurring as much measurement debt as possible.

Three principles of software development effectiveness metrics

Now that we’ve explored the question of what constitutes an appropriate software development effectiveness metric and ways to quickly identify them, I hope to give more recommended metrics based on the business situation and the defined team context through three principles developed through observation.

Principle #1: Don't let the measurement become the target

The economist Charles Goodhart proposed Goodhart’s Law in 1975: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” For example, when the French colonial government in Vietnam tried to cull the rat population by putting a bounty on their tails, it only encouraged people to breed more rats so that they could cut their tails and pocket the reward. While “the number of rats’ cut tails” usually positively correlates with “the number of dead rats,” which is a good metric, turning the former into the optimization goal led to the inverse intended effect. In our experience, the same principle applies to the field of software development.

When you measure and set the number of story points that the team needs to accomplish in each iteration, the team will be driven to split the story into more cards than usual to reach the goal. This can manifest in several ways. For example, the team might end up with a three-point Team Building card on the wall after measurement because they want to get more story points for each iteration. Estimates can also change once measurement is done, such as the estimate for database creation going from one point to three points. Or, the team could decide to move a card back to the Backlog when it is blocked by third-party dependencies, to avoid having to continuously identify and push it back, thus increasing cycle time. The target might have been reached, but will this kind of measurement bring value to the business? Can it be implemented into specific management or technical practices?

To make metrics and data collection as realistic as possible, we need to focus on trends and blockages. In the above case, what’s needed is to observe the trends of the number of completed cards in each iteration. Generally, the cards completed in each iteration fluctuate within a reasonable range, but observing the overall trend should let us identify the blockages and their causes and take targeted treatments to accelerate the flow of cards. There’s no need to compare yourself with other teams, setting a target wildly would cause unexpected results.

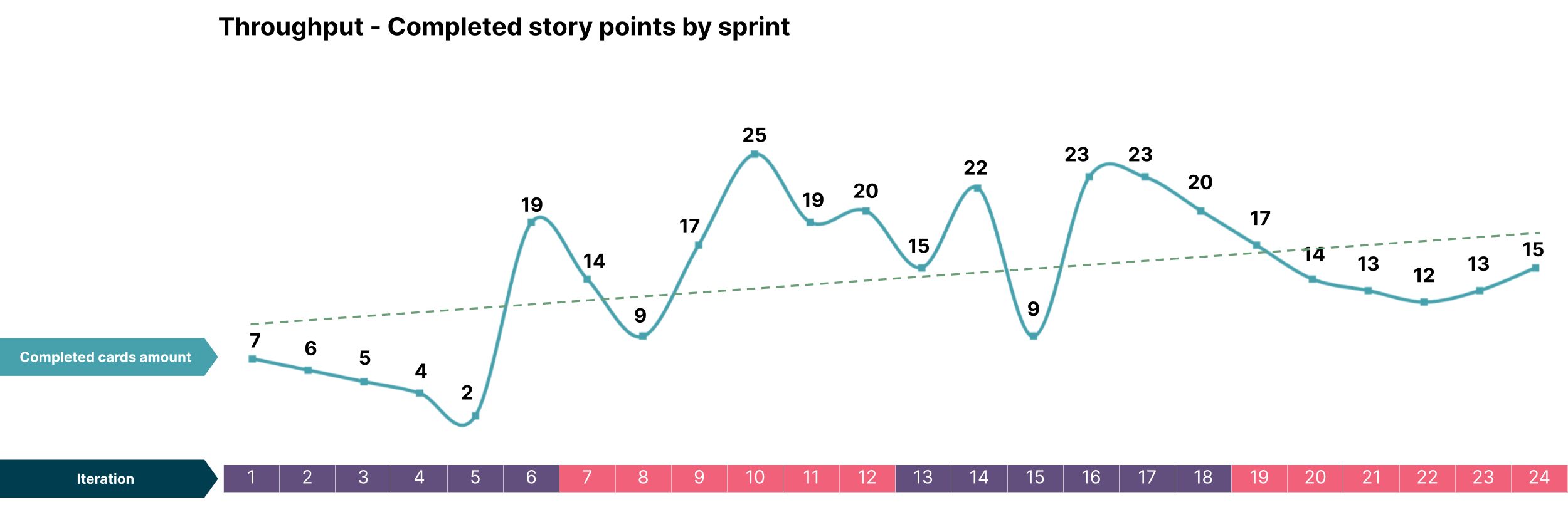

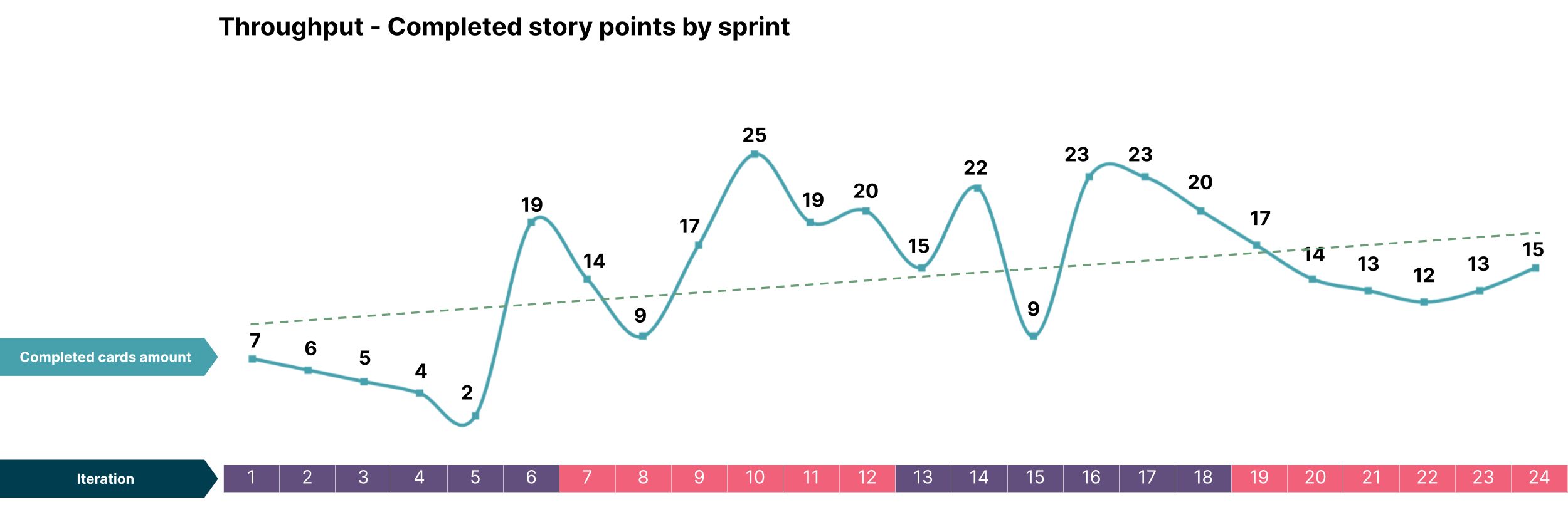

From the chart above, which represents the number of story card points completed in each iteration of a 24-iteration project, we can analyze the project's effectiveness:

Overall trend is of a gradual increase, indicating that the team is becoming more proficient over time.

Drop between iterations seven and eight indicates that the story card is too large, leading to increased complexity of communication and development time. Solution: the developers communicate more closely with the business analysts to have smaller and more independent story cards from the beginning.

Drop between iterations 14 and 15 was caused by problems with the third-party API, which led to cards with a cumulative total of more than 10 points having their delivery delayed to the next iteration. Solution: closely track the status of dependent systems to adjust development tasks and prevent blocks and excessive waiting.

Principle #2: A metric that cannot be decomposed is not a good metric

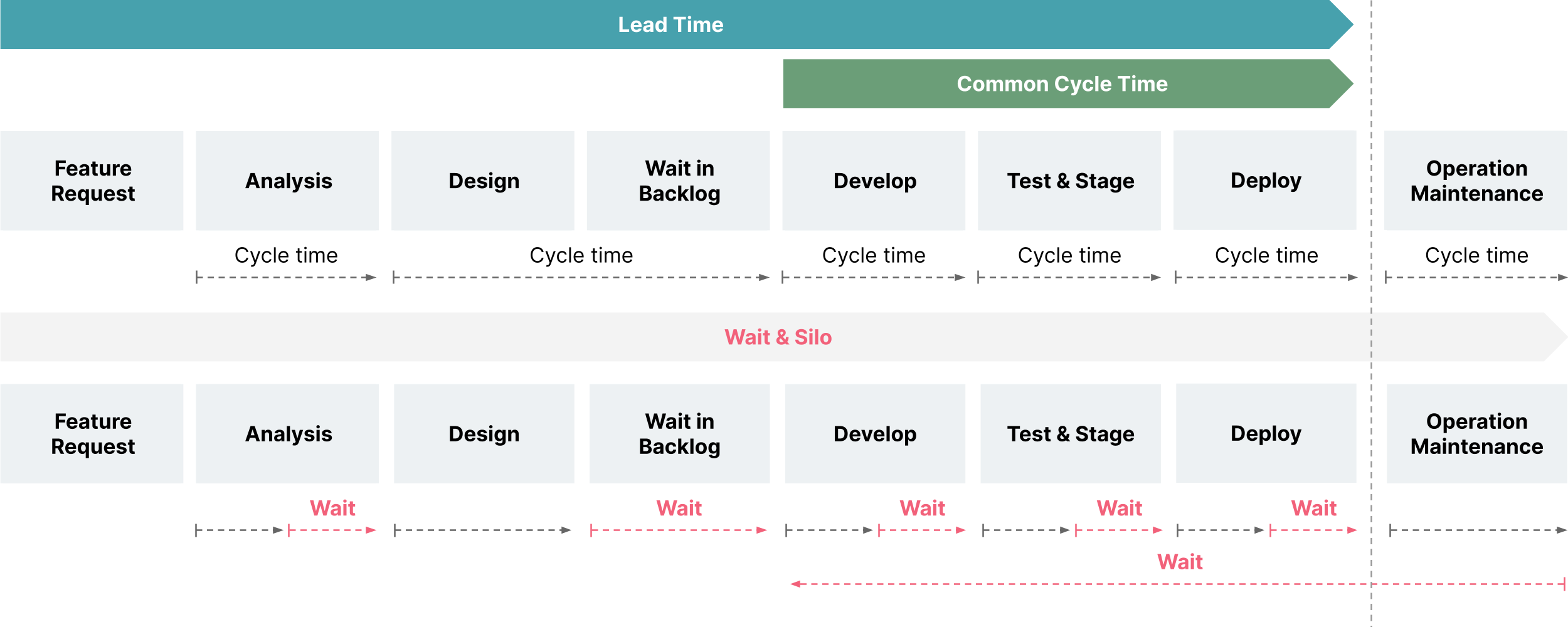

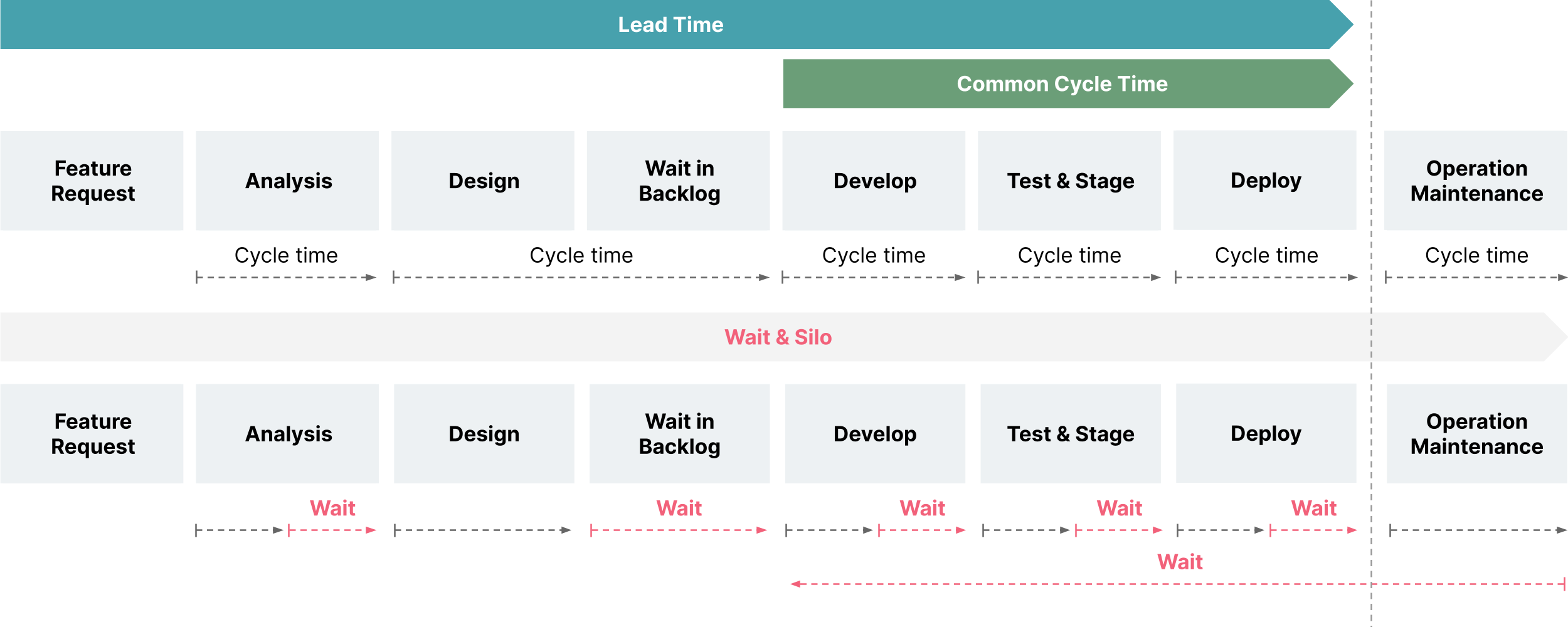

Metrics and results that can be decomposed are good metrics. An example of such a metric is lead time for change or feature delivery time, as they can facilitate the delivery of value flow. However, it can be difficult to capture the moment when the requirement is raised and the moment when the feature goes online and to calculate the time between those two points for measurement and block identification, because of the large span between the two and the numerous factors involved. As such, getting a clear view of the causes of blockages is not easy.

The DuPont analysis is a classic application of problem decomposition. It decomposes a large and hard to visualize problem into several sub-problems, then analyzes them to solve the original big problem. This model can also be applied to development effectiveness. Metrics can be measured and decomposed in stages, and each stage can be further subdivided.

Decomposing the feature delivery time lets us find more optimization points throughout. Look for features of similar size in the last iteration, and also decompose the time and proportion of each process metric, observing whether each metric increases or decreases per iteration. For example, the feature design time increased by 2.18% compared with the similarly sized feature in the previous iteration. What caused this? Can it be improved? As it turns out, it was due to a lack of thorough analysis, which led to multiple design revisions as feedback was received, leading to a delay. Solution: add a clearer checklist for the output of the feature analysis to ensure that it has been thoroughly analyzed before being sent to design. This shows the way in which a decomposable metric can be applied to management and technical practices.

Principle #3: Only the measurement of sustainable expansion can drive the efficiency of the value flow

The measurement of development effectiveness often starts with a more global metric, such as feature delivery time, as it can more intuitively reflect the business value. However, metrics can also start locally and drive the increasing efficiency of the value flow through continuous expansion. Let’s take as an example lead time, which measures the time from code commits to the deployment to the production environment. In the second chapter of "Accelerate," Forsgren gives the following description: "Lead time is the time it takes to go from a customer making a request to the request being satisfied. . . In the design part of the lead time, it's often unclear when to start the clock, and often there is high variability. . . However, the delivery part of the lead time — the time it takes for work to be implemented, tested, and delivered — is easier to measure and has a lower variability.”

What this passage illustrates is that we should only use lead time as a starting metric, as while a short lead time indicates that the team has strong engineering practices and impeccable CI/CD (continuous integration/continuous delivery), it doesn't necessarily mean an ability to quickly respond to customer needs. We should continuously expand metrics to drive the value flow efficiency.

Let’s look at an actual case: the team measured the lead time for change, which usually takes about 10 minutes. However, it took several days for some code commits to be deployed. The code had entered the pull request review phase after commit, meaning it needed to be reviewed by the client team. When they didn’t do this in time, it didn’t trigger the pipeline, leading to a delay of a few days. The pull requests that the team could review and merge by themselves had been reviewed and merged quickly, so the team extended the measurement of the lead time for change. The start time moved left from the time when merging to the master branch to the first code commit in the pull request. The points that could be optimized in the process of pull request review in coordination with the client team were found through measurement, accelerating the process of pull request.

Later, the start time of the lead time for change was moved further left to the time when the story card was moved into the development column. When the story was moved into the development column, it triggered the start of the counter for the lead time for change, helping us identify potential blockages in communication with BA/QA and points that can be further optimized. If the developed feature is protected by the feature toggle and the feature toggle is not turned on after the code is committed and deployed, the end time of the lead time can also be shifted right to the time when the feature toggle is turned on. Then it can be analyzed to see whether the business decision-making time is excessive to the point of affecting features going online.

I hope these three principles will help you in the process of using metrics for development effectiveness:

Don't let the measurement become a target. To make metrics and data collection as realistic as possible, we need to focus on trends and blockages.

A metric that cannot be decomposed is not a good metric.

Only the measurement of sustainable expansion can drive the efficiency of the value flow.