Novelty is not Innovation

The pressures of the changing market have compounded that confusion with the desire to do anything, instead of the right thing. In the arms race for what’s-new, too often innovation at scale becomes a synonym for “expensive diversion.”

Whether incremental or disruptive, enterprise innovation has to be relevant by being repeatable. Innovation must be rooted in the core competencies of an organization; their product portfolios must be a mirror of an organization’s value proposition.

Maintaining competitive advantage when the shelf life of a product has shortened requires producing change-making, unique products regularly a core capability of any enterprise.

Changes

This market is changing, and the customers are the ones changing it.

The Arms Race, and its Insanities

Their solution is briefly new, but often not novel, and rarely innovative.

Eventually that paralysis can so severely affect an organization without a repeatable innovation capability that its value proposition becomes vulnerable and less relevant, forcing “bet the business” change initiatives. Innovation moves from being desirable to being critical, but the capability to get there is just as bad as it’s been.

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. The inverse proposition also appears to be true: a complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be made to work.”

Under Pressure

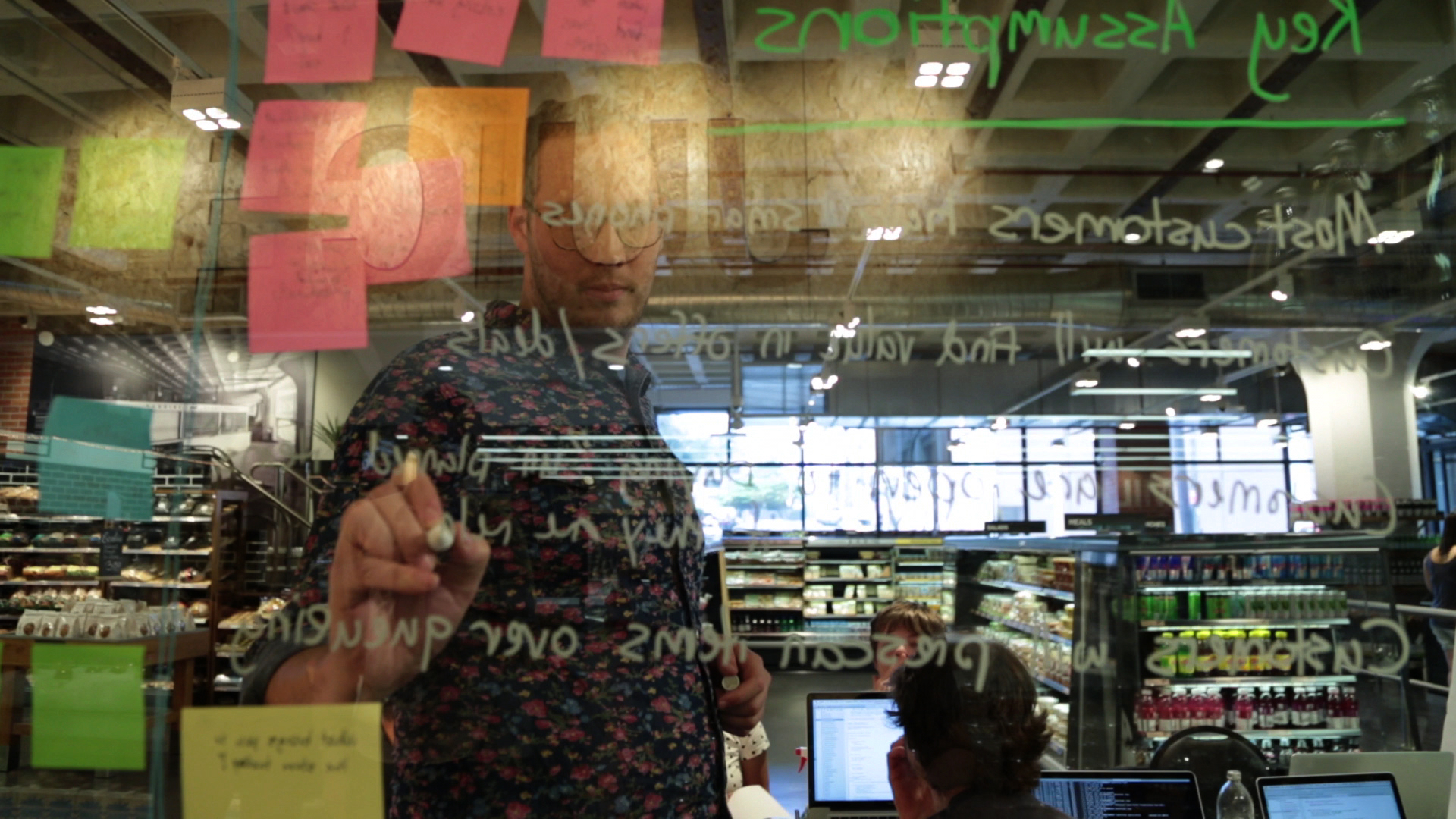

Finding that fit requires discovery, iteration, and being wrong just enough to be right.

Doing Innovation Right

2. Quick Pursuit - Endless research and experimentation won’t build more confidence, though. It generates noise and delays releasing a product to the point the opportunity may be gone. We quickly scale up using the scaffolds from discovery to pursue the market opportunity we’ve identified. Building a testable and viable product requires the discipline to focus on what makes a product unique in the market and innovative to its users.

It’s the work of weeks, not months and quarters. Transparent, collaborative development practices get a product into the hands of customers quickly.

3. Test, Learn, Pivot - Lean product development relies on getting just-enough information at the right time. During the discovery phase, determine that real needs exist in the market and that the organization is uniquely suited to addressing that need. A response to that need can then be built, and using customer feedback and usability test results, tailor and increase the efficacy of the solution. Experiment with real customers to get ideas to market quickly.

4. Ongoing Discovery - I’ve already discussed how the market is changing, and how customers and users are driving that change. Discovery needs to be more than a point on a timeline; it’s an ongoing activity that increases the value and defensible position of a innovative product. Having rapid responses to changes is useless without the information and insight to respond to — discovery keeps teams plugged in and empathetic to customer need. Greater empathy and engagement with the market creates products with better and most lasting fit.

5. Scaling and Evolving the Opportunity - Discovering that a product’s value proposition has applicability in adjacent customer segments or even vertical industries is a precious opportunity to scale and evolve the offering. Explore, diverge, and discover applicable solutions, how to grow an innovative product offering into a core competency, and how to defend its market positioning.

Stop Confusing Novelty for Innovation

Break Away

Experiment with your ideas quickly; build empathy with the customer and understand their motivations. Tightly relating an innovative products offering with customer need builds a strong and defensible market fit.

Develop just-enough solutions at the right level of maturity to pursue the opportunity with a rapid response. Understand when to advance to the next stage, what the right level of confidence looks like, and how being first and being successful can co-exist.

Continually listen to your customers, how they use your product, why they’re interested in a competitor’s offering. Learn from everything, but only respond to the smart things.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.