How much can you carry? A study in capacity modelling.

People, unlike machines, don’t work at uniform rates. This is especially true when we are doing ‘thinking-work’. We often need time to prepare work. We need breaks. And our different levels of competency and experience naturally means the same piece of work will take different amounts of time depending on the person doing the work.

Thinking About Capacity

So how should we think about our capacity in a more realistic way? And why is it important to know our capacity in a working environment? I’ll try to answer the second question first and then talk about a useful approach to modelling capacity in a work environment.

- Whether we are working in a team or working on our own, we need to have an understanding of our capacity so that we know what work we think we can take on in a set period of time. The problem is that we humans are inherently optimistic and we often have unrealistic expectations about what we think we can do.

Like filling our plate at the all-you-can-eat buffet, estimating our capacity allows us to determine what we think we can realistically carry on our plate without everything falling off. This is even more important where other work is dependent on our work being completed.

- Second, having a realistic view of capacity can allow a team or an individual to identify upcoming constraints that can be addressed before they materially affect the work. Constraints may exist because a single person has essential specialist skills or there is an increase in a type of work that requires a certain skill. Knowing this in advance, we can bring in additional people, invest in training and cross-skilling, or re-sequence work to minimise the impact of the perceived capacity constraints.

- And finally, the process of determining capacity can reveal hidden waste and non-value added work that can be eliminated, automated, optimised or delegated to maximise our opportunity to do more valuable work. We would all like to feel that the work we do is useful so having a view on the proportion of valuable versus non-value work we are doing allows us to start eliminating work that contributes no value.

Creating a Model

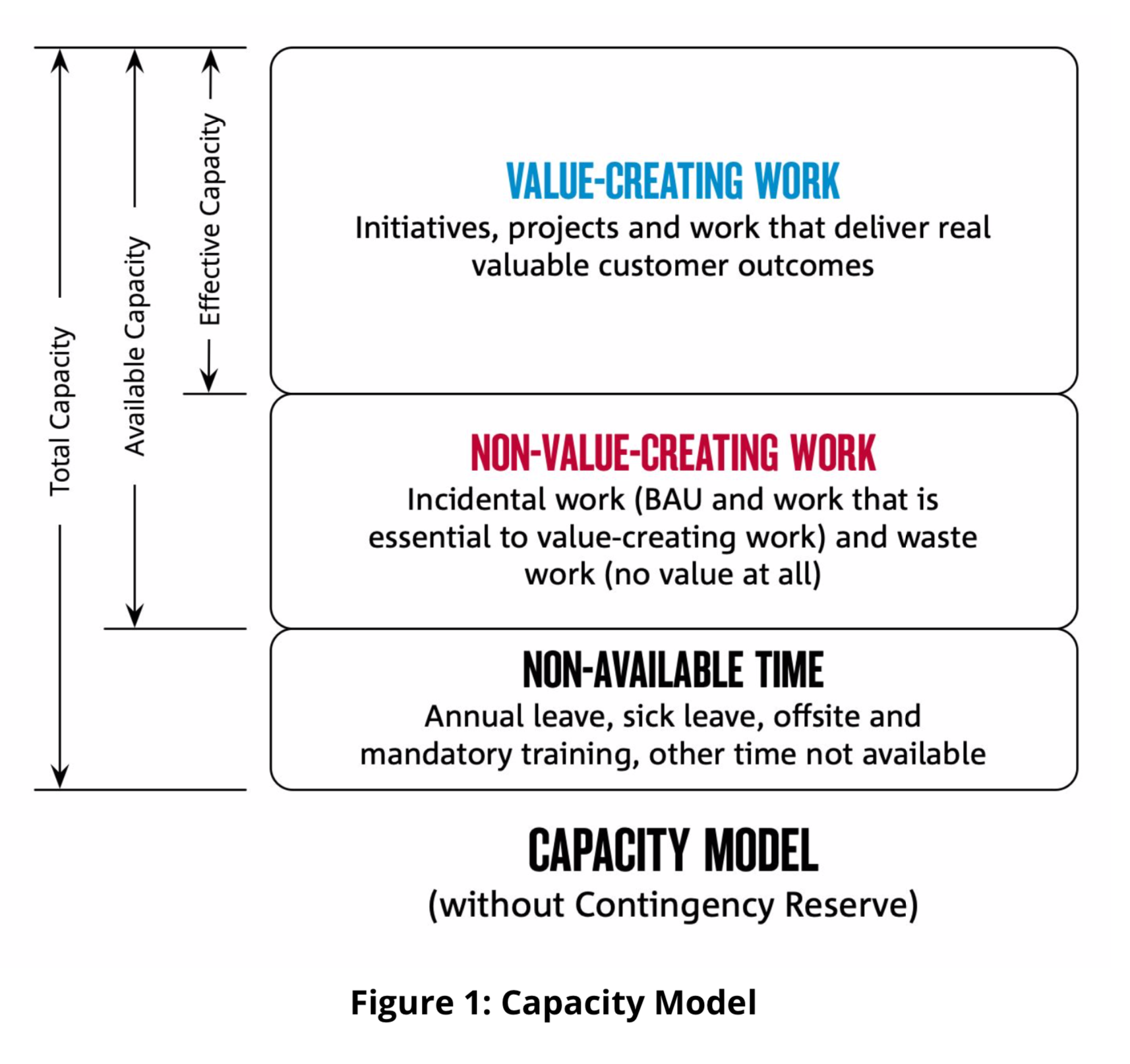

So that’s why it’s important to know our capacity to do work. But how should we model capacity in a way that helps us better understand what we can do? Breaking down capacity into logical pieces and visualising each piece seems to help and here's one way to think about the pieces. Keep in mind that all models are wrong but hopefully this kind of model is useful.

-

Total capacity is easy to calculate; number of working hours in a day x number of days in a working period, say, two or four weeks. But we know that we can’t possibly work all the working hours in a day so we have to start breaking down the total capacity into logical pieces.

-

Available capacity is the capacity we have to do work after we subtract unavailable time like non-working days, annual and long service leave, mandatory training and other time away. This is usually quite easy to do because we know when we won’t be available to do work. What’s left is a realistic view of the amount of time we can possibly do work - what we can call our available capacity.

- Effective capacity is calculated by subtracting non-value creating work (work that doesn't create direct value but may be necessary to support value-creating work) from our available capacity. What’s left is our capacity to do valuable work according to its priority of value. Simply doing this exercise can identify huge chunks of time and effort being spent on non-value creating work which we can critically analyse as necessary (incidental work required to support value-creating work) or unnecessary (pure waste that adds no value at all).

Now that we know our available and effective capacity, we want to use this information to plan work. But there’s one more step to take before we use the information to plan work.

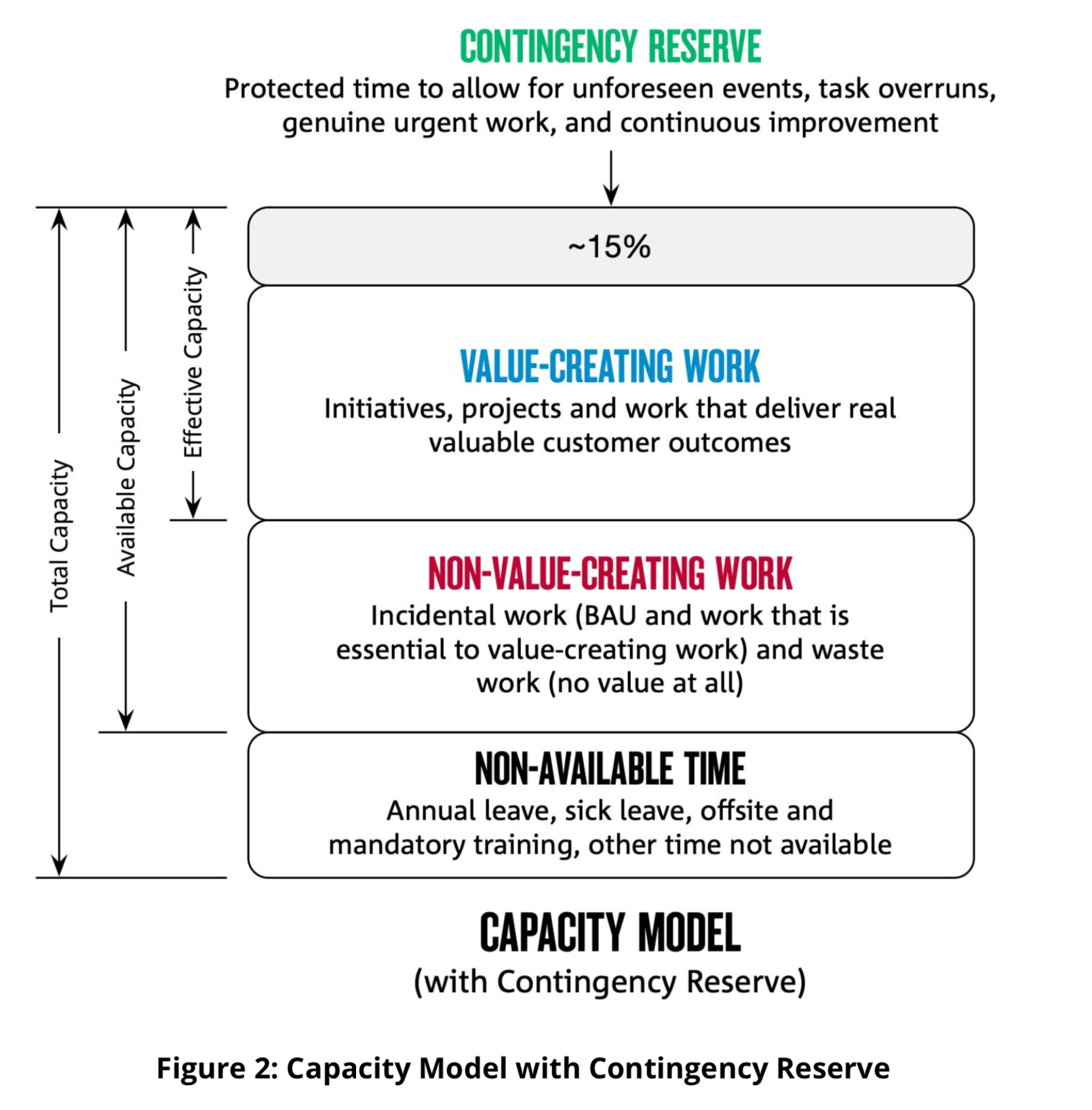

It is well known that when a road fills to capacity with cars, the cars create a traffic jam and everyone slows down. Similarly, planning our work to 100% capacity actually slows everything down because there's no slack or wiggle room when our estimations or best efforts turn out to be different from reality. So while we work to 100% of our available capacity, we should not fill the road with cars and plan to 100%.

To do this in practice, we want to reserve a small amount of time from our available capacity for contingencies. This contingency reserve is typically about 10% to 15% and it is time we set outside our work plan. The contingency reserve serves four purposes:

- It provides a buffer for work that is planned to be completed in the current WIP iteration but takes longer than estimated - task overruns.

- It allows us to respond to genuinely urgent work while minimising the possible disruption to our work plan. Note: Care needs to be taken to avoid this reserve being used by other groups to get work done early.

- It allows us to accommodate an unplanned event such as sick and carers leave and late notification of events (town halls, office planning sessions, etc).

- And in the event that the reserve (or part of the reserve) remains unused near the end of the WIP iteration, it gives us the ability to do some work practices improvement, do some background or preparation work to support future work, or pull work forward from the next work iteration.

Summary

By describing our capacity in terms of available and non-available time as well as different types of work, we start to build an understanding of our true(r) capacity. Once we have this view, we can develop a clear, forward looking plan of what we think can be done in the next iteration of work.

Reserving a portion of protected, unallocated time to allow us to accommodate variations from estimates, respond to unforeseen events, address unplanned urgent work, and do continuous improvement on our work practices and methods.

And using the capacity model we are better equipped to identify upcoming prioritised work that might be affected by our capacity constraints or dependencies and allow us to mitigate it or prevent the constraint affecting our work.

Disclaimer: The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Thoughtworks.